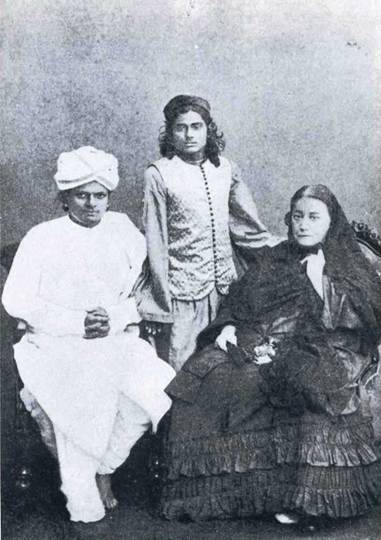

Helena Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (12 August [O.S. 31 July] 1831 – 8 May 1891), often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian and American mystic and author who co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. She gained an international following as the leading theoretician of Theosophy.

Early life

The accounts of her early life provided by her family members have also been considered dubious by biographers.

Blavatsky was born as Helena Petrovna Hahn von Rottenstern in the town of Yekaterinoslav, then part of the Russian Empire. Her birth date was 12 August 1831, although according to the Julian calendar used in 19th-century Russia it was 31 July. Immediately after her birth, she was baptized into the Russian Orthodox Church. At the time, Yekaterinoslav was undergoing a cholera epidemic, and her mother contracted the disease shortly after childbirth; despite the expectations of their doctor, both mother and child survived the epidemic.

Blavatsky's family was aristocratic. Her mother was Helena Andreyevna Hahn von Rottenstern, a self-educated 17-year-old who was the daughter of Princess Yelena Pavlovna Dolgorukaya, a similarly self-educated aristocrat. Blavatsky's father was Pyotr Alexeyevich Hahn von Rottenstern, a descendant of the German Hahn aristocratic family, who served as a captain in the Russian Royal Horse Artillery, and would later rise to the rank of colonel.

In 1838, Blavatsky's mother moved with her daughters to be with her husband at Poltava, where she taught Blavatsky how to play the piano and organized for her to take dance lessons. As a result of her poor health, Blavatsky's mother returned to Odessa, where Blavatsky learned English from a British governess.

Marriage

At age 17, she agreed to marry Nikifor Vladimirovich Blavatsky, a man in his forties who worked as Vice Governor of Erivan Province. Her reasons for doing so were unclear, although she later claimed that she was attracted by his belief in magic. Although she tried to back out shortly before the wedding ceremony, the marriage took place on 7 July 1849. Moving with him to the Sardar Palace, she made repeated unsuccessful attempts to escape and return to her family in Tiflis, to which he eventually relented.

She claims that during one of her many escape attempts, she ended up in Constantinople and then journeyed around the world, visiting all of Asia, Africa, and even America. However, there is no record or evidence to confirm these travels and the fanciful nature of her stories (washing up on shore in England after a shipwreck) make it likely these stories are fabrications.

Arrival in New York

Blavatsky left her family in Odessa, in April 1873. She spent time in Bucharest and Paris, before arriving in New York City on 8 July 1873. There, she moved into a women's housing cooperative on Madison Street in Manhattan's Lower East Side, earning a wage through piece work sewing and designing advertising cards.

Soon after her arrival in New York, Blavatsky received news of her father's death, thus inheriting a considerable fortune, allowing her to move into a lavish hotel. In December 1874, Blavatsky met the Georgian Mikheil Betaneli. Infatuated with her, he repeatedly requested that they marry, to which she ultimately relented; this constituted bigamy, as her first husband was still alive. However, as she refused to consummate the marriage, Betaneli sued for divorce and returned to Georgia.

The Theosophical Society

Blavatsky was intrigued by a news story about William and Horatio Eddy, brothers based in Chittenden, Vermont, who it was claimed could levitate and manifest spiritual phenomena. She visited Chittenden in October 1874, there meeting the reporter Henry Steel Olcott, who was investigating the brothers' claims for the Daily Graphic. Claiming that Blavatsky impressed him with her own ability to manifest spirit phenomena, Olcott authored a newspaper article on her. They soon became close friends, giving each other the nicknames of "Maloney" (Olcott) and "Jack" (Blavatsky).

He helped attract greater attention to Blavatsky's claims, encouraging the Daily Graphics editor to publish an interview with her, and discussing her in his book on Spiritualism, People from the Other World (1875), which her Russian correspondent Alexandr Aksakov urged her to translate into Russian. She began to instruct Olcott in her own occult beliefs, and encouraged by her he became celibate, tee-totaling, and vegetarian, although she herself was unable to commit to the latter.

At a Miracle Club meeting on 7 September 1875, Blavatsky, Olcott, and Irish Spiritualist, William Quan Judge, agreed to establish an esoteric organization, with Charles Sotheran suggesting that they call it the Theosophical Society. The term theosophy came from the Greek theos ("god(s)") and sophia ("wisdom"), thus meaning "god-wisdom" or "divine wisdom." The term was not new, but had been previously used in various contexts by the Philaletheians and the Christian mystic, Jakob Böhme. Theosophists would often argue over how to define Theosophy, with Judge expressing the view that the task was impossible. Blavatsky however insisted that Theosophy was not a religion in itself. Lachman has described the movement as "a very wide umbrella, under which quite a few things could find a place."

Isis Unveiled

In 1875, Blavatsky began work on a book outlining her Theosophical worldview, much of which would be written during a stay in the Ithaca home of Hiram Corson, a Professor of English Literature at Cornell University. While writing it, Blavatsky claimed to be aware of a second consciousness within her body, referring to it as "the lodger who is in me", and stating that it was this second consciousness that inspired much of the writing. In Isis Unveiled, Blavatsky quoted extensively from other esoteric and religious texts, although her contemporary and colleague Olcott always maintained that she had quoted from books that she did not have access to.

Revolving around Blavatsky's idea that all the world's religions stemmed from a single "Ancient Wisdom," which she connected to the Western esotericism of ancient Hermeticism and Neoplatonism, it also articulated her thoughts on Spiritualism, and provided a criticism of Darwinian evolution, stating that it dealt only with the physical world and ignored the spiritual realms.

The book was edited by Professor of Philosophy Alexander Wilder and published in two volumes by J.W. Bouton in 1877. Although facing negative mainstream press reviews, including from those who highlighted that it extensively quoted around 100 other books without acknowledgement, it proved to be such a commercial success, with its initial print run of 1,000 copies selling out in a week, that the publisher requested a sequel, although Blavatsky turned down the offer. While Isis Unveiled was a success, the Society remained largely inactive, having fallen into this state in autumn 1876. In July 1878, Blavatsky gained U.S. citizenship.

Move to India

Unhappy with life in the U.S., Blavatsky decided to move to India, with Olcott agreeing to join her, securing work as a U.S. trade representative to the country. They left New York City aboard the Canada, arriving in Bombay in February 1879.

In July 1879, Blavatsky and Olcott began work on a monthly magazine, The Theosophist, with the first issue coming out in October. The magazine soon obtained a large readership. Blavatsky and Olcott were then invited to Ceylon by Buddhist monks. There they officially converted to Buddhism – apparently the first from the United States to do so. Touring the island, they were met by crowds intrigued by these unusual Westerners who embraced Buddhism rather than proselytizing Christianity.

Blavatsky was then invited to Simla to spend more time with Alfred Percy Sinnett, the editor of The Pioneer and a keen Spiritualist. While there, she performed a range of materializations that astounded the other guests; in one instance, she allegedly made a cup-and-saucer materialize under the soil during a picnic. Sinnett was eager to contact the Ascended Masters himself, convincing Blavatsky to facilitate this communication, resulting in the production of over 1400 pages allegedly authored by Koot Hoomi and Morya, which came to be known as the Mahatma Letters.

Theosophy was unpopular with both Christian missionaries and the British colonial administration, with India's English-language press being almost uniformly negative toward the Society. The group nevertheless proved popular, and branches were established across the country. While Blavatsky had emphasized its growth among the native Indian population rather than among the British elite, she moved into a comfortable bungalow in the elite Bombay suburb of Breach Candy, which she said was more accessible to Western visitors.

Blavatsky was diagnosed with Bright's disease, and hoping the weather to be more conducive to her condition she took up the offer of the Society's Madras Branch to move to their city. However, in November 1882 the Society purchased an estate in Adyar, which became their permanent headquarters; a few rooms were set aside for Blavatsky, who moved into them in December. She continued to tour the subcontinent, claiming that she then spent time in Sikkim and Tibet, where she visited her teacher's ashram for several days.

Worsening health led Blavatsky to contemplate a return to the milder climate of Europe, and resigning her position as corresponding secretary of the society, she left India in March 1885.

Final years in Europe

Settling in Naples, Italy, in April 1885, she began living off of a small Society pension and continued working on her next book, The Secret Doctrine. She then moved to Würzburg in the Kingdom of Bavaria, where she was visited by a Swedish Theosophist, the Countess Constance Wachtmeister, who became her constant companion throughout the rest of her life. In December 1885, the SPR published their report on Blavatsky and her alleged phenomena, authored by Richard Hodgson. In his report, Hodgson accused Blavatsky of being a spy for the Russian government, further accusing her of faking paranormal phenomena, largely on the basis of the Coulomb's claims. The report caused much tension within the Society, with a number of Blavatsky's followers – among them Babaji and Subba Row – denouncing her and resigning from the organization on the basis of it.

In 1886, by which time she was using a wheelchair, Blavatsky moved to Ostend in Belgium, where she was visited by Theosophists from across Europe. Supplementing her pension, she established a small ink-producing business. She received messages from members of the Society's London Lodge who were dissatisfied with Sinnett's running of it; they believed that he was focusing on attaining upper-class support rather than encouraging the promotion of Theosophy throughout society, a criticism Blavatsky agreed with. In September 1887, she moved into the Holland Park home of fellow Theosophists, Bertram Keightley and his nephew Archibald Keightley.

In London, Blavatsky founded a magazine, controversially titling it Lucifer; in this Theosophical publication she sought to completely ignore claims regarding paranormal phenomena, and focus instead on a discussion of philosophical ideas.

Death

In the winter of 1890, Britain had been afflicted by an influenza epidemic (the global 1889–1890 flu pandemic), with Blavatsky contracting the virus. It led to her death on the afternoon of 8 May 1891, in Besant's house. The date would come to be commemorated by Theosophists ever since as White Lotus Day. Her body was cremated at Woking Crematorium on 11 May.

Personal life

The biographer Peter Washington described Blavatsky as "a short, stout, forceful woman, with strong arms, several chins, unruly hair, a determined mouth, and large, liquid, slightly bulging eyes." She had distinctive azure-colored eyes, and was overweight throughout her life.

Blavatsky's sexuality has been an issue of dispute; many biographers have believed that she remained celibate throughout her life, with Washington believing that she "hated sex with her own sort of passion." In later life she stated that she was a virgin, although she had been married to two men during her lifetime.

In later life, she was known for wearing loose robes, and wore many rings on her fingers. She was a heavy cigarette smoker throughout her life, and was known for smoking hashish at times. She lived simply and her followers believed that she refused to accept monetary payment in return for disseminating her teachings. Blavatsky preferred to be known by the initialism "HPB"," a sobriquet applied to her by many of her friends which was first developed by Olcott. She avoided social functions and was scornful of social obligations. She spoke Russian, Georgian, English, French, Italian, Arabic, and Sanskrit.

Biographer Marion Meade referred to her as "an eccentric who abided by no rules except her own."