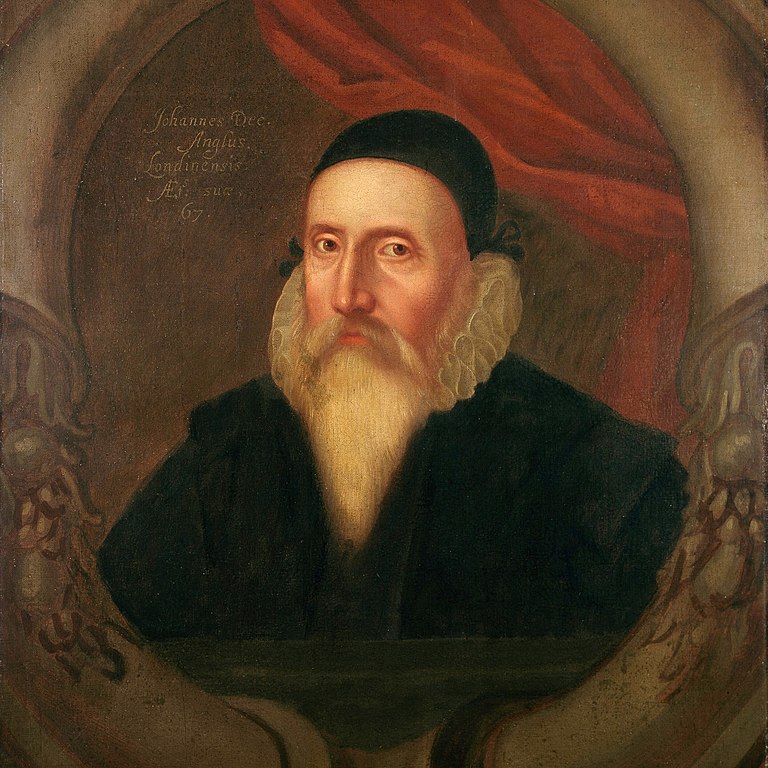

John Dee

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, teacher, occultist, and alchemist. He was the court astronomer for, and advisor to, Elizabeth I, and spent much of his time on alchemy, divination and Hermetic philosophy. As an antiquarian, he had one of the largest libraries in England at the time.

Early life

Dee was born in Tower Ward, London, to Rowland Dee, of Welsh descent, and Johanna, daughter of William Wild. His surname "Dee" reflects the Welsh du (black). His grandfather was Bedo Ddu of Nant-y-groes, Pilleth, Radnorshire; John retained his connection with the locality. His father Roland was a mercer and gentleman courtier to Henry VIII. John Dee claimed descent from Rhodri the Great, King of Wales, and constructed a pedigree accordingly. His family had arrived in London with Henry Tudor's coronation as Henry VII.

Dee attended Chelmsford Chantry School (now King Edward VI Grammar School) from 1535 to 1542. He entered St John's College, Cambridge in November 1542, aged 15, graduating BA in 1545 or early 1546.

In 1555, Dee was arrested and charged with the crime of "calculating", because he had cast horoscopes of Queen Mary and Princess Elizabeth. The charges were raised to treason against Mary. Dee appeared in the Star Chamber and exonerated himself, but was turned over to the Catholic Bishop Bonner for religious examination.

Court astrologer

When Elizabeth succeeded to the throne in 1558, Dee became her astrological and scientific advisor. He chose her coronation date and even became a Protestant. From the 1550s to the 1570s, he served as an advisor to England's voyages of discovery, providing technical aid in navigation and political support to create a "British Empire", a term he was the first to use. From 1570, Dee advocated a policy of political and economic strengthening of England and establishment of colonies in the New World.

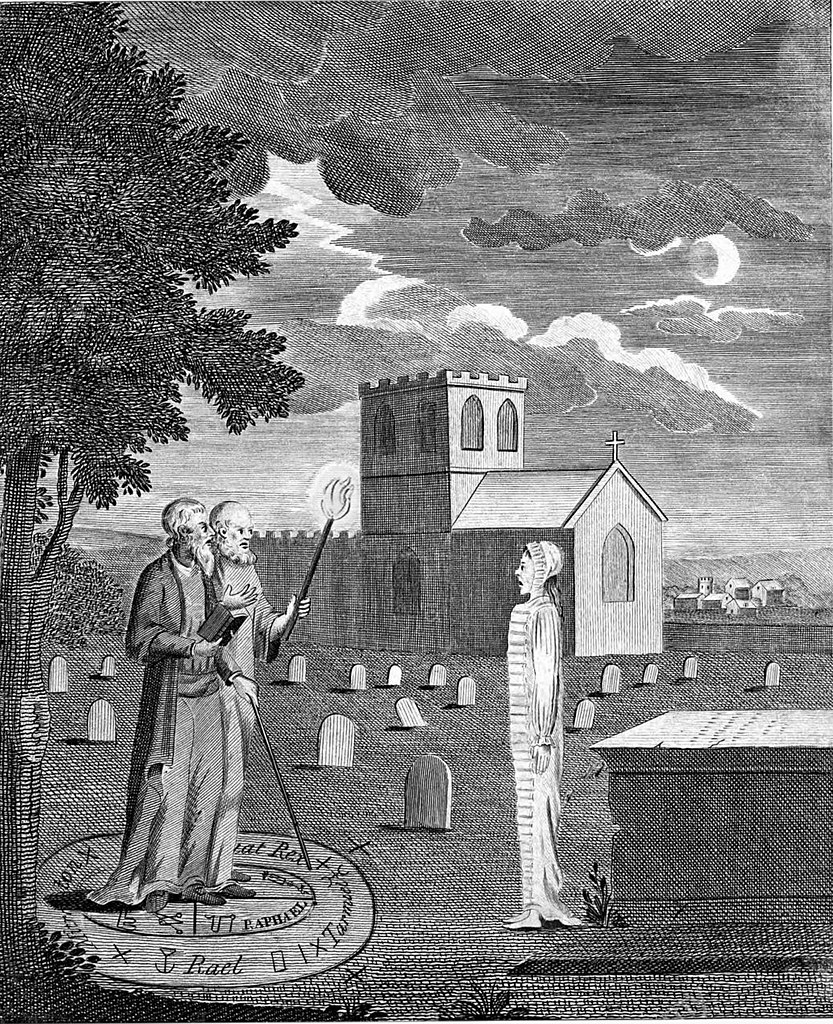

Work with Edward Kelley

By the early 1580s, Dee was discontented with his progress in learning the secrets of nature and his diminishing influence and recognition in court circles. Failure of his ideas concerning a proposed calendar revision, colonial establishment and ambivalent results for voyages of exploration in North America had nearly brought his hopes of political patronage to an end. He subsequently began to turn energetically towards the supernatural as a means to acquire knowledge. He sought to contact spirits through the use of a "scryer" or crystal-gazer, which he thought would act as an intermediary between himself and the angels.

Dee's first attempts with several scryers were unsatisfactory, but in 1582 he met Edward Kelley (then calling himself Edward Talbot to disguise his conviction for "coining" or forgery), who impressed him greatly with his abilities. Dee took Kelley into his service and began to devote all his energies to his supernatural pursuits. These "spiritual conferences" or "actions" were conducted with intense Christian piety, always after periods of purification, prayer and fasting. Dee was convinced of the benefits they could bring to mankind. The character of Kelley is harder to assess: some conclude that he acted with cynicism, but delusion or self-deception cannot be ruled out. Kelley's "output" is remarkable for its volume, intricacy and vividness. Dee records in his journals that angels dictated several books to him this way, through Kelley, some in a special angelic or Enochian language.

Travels through Europe

In 1583, Dee met the impoverished yet popular Polish nobleman Albert Łaski, who, after overstaying his welcome at court, invited Dee to accompany him back to Poland. With some prompting by the "angels" (again through Kelley) and by dint of his worsening status at court, Dee decided to do so. He, Kelley, and their families left in September 1583, but Łaski proved to be bankrupt and out of favour in his own country.

Dee and Kelley began a nomadic life in Central Europe, meanwhile continuing their spiritual conferences, which Dee detailed in his diaries and almanacs. They had audiences with Emperor Rudolf II in Prague Castle and King Stephen Bathory of Poland, whom they attempted to convince of the importance of angelic communication. The Bathory meeting took place at the Niepołomice Castle (near Kraków, then capital of Poland) and was later analysed by Polish historians (Ryszard Zieliński, Roman Żelewski, Roman Bugaj) and writers (Waldemar Łysiak).

While Dee was generally seen as a man of deep knowledge, he was mistrusted for his connection with the English monarch, Elizabeth I, for whom some thought (and still do) that Dee was a spy. The Polish king, a devout Catholic and cautious of supernatural mediators, began their meeting(s) by affirming that prophetic revelations must match the teachings of Christ, the mission of the Holy Catholic Church, and the approval of the Pope.

In 1587, at a spiritual conference in Bohemia, Kelley told Dee that the Archangel Uriel had ordered the men to share all their possessions, including their wives. By this time, Kelley had gained some renown as an alchemist and was more sought-after than Dee in this regard: it was a line of work that had prospects for serious and long-term financial gain, especially among the royal families of central Europe. Dee, however, was more interested in communicating with angels, who he believed would help him solve the mysteries of the heavens through mathematics, optics, astrology, science and navigation.

The order for wife-sharing caused Dee anguish, but he apparently did not doubt it was genuine and they apparently shared wives. However, Dee broke off the conferences immediately afterwards. He returned to England in 1589, while Kelley went on to be the alchemist to Emperor Rudolf II. Nine months later, on 28 February 1588, a son was born to Dee's wife, whom Dee baptised Theodorus Trebonianus Dee and raised as his own.

Final years

Dee returned to Mortlake after six years abroad to find his home vandalised, his library ruined and many of his prized books and instruments stolen. Furthermore, he found that increasing criticism of occult practices had made England still less hospitable to his magical practices and natural philosophy. He sought support from Elizabeth, who hoped he could persuade Kelley to return and ease England's economic burdens through alchemy. She finally appointed Dee Warden of Christ's College, Manchester, in 1595.

This former College of Priests had been re-established as a Protestant institution by Royal Charter in 1578. However, he could not exert much control over its fellows, who despised or cheated him. Early in his tenure, he was consulted on the demonic possession of seven children, but took little interest in the case, although he allowed those involved to consult his still extensive library.

Dee left Manchester in 1605 to return to London, but remained Warden until his death. By that time, Elizabeth was dead and James I gave him no support. Dee spent his final years in poverty at Mortlake, forced to sell off various possessions to support himself and his daughter, Katherine, who cared for him until his death in Mortlake late in 1608 or early in 1609 aged 81. In 2013 a memorial plaque to Dee was placed on the south wall of the present church.