Difference between revisions of "Necromancy"

Occultwiki (talk | contribs) |

Occultwiki (talk | contribs) (added divination category) |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

[[Category:Methods of Divination]] | [[Category:Methods of Divination]] | ||

[[Category:Featured Articles]] | [[Category:Featured Articles]] | ||

[[Category:Divination]] | |||

Revision as of 08:38, 7 October 2022

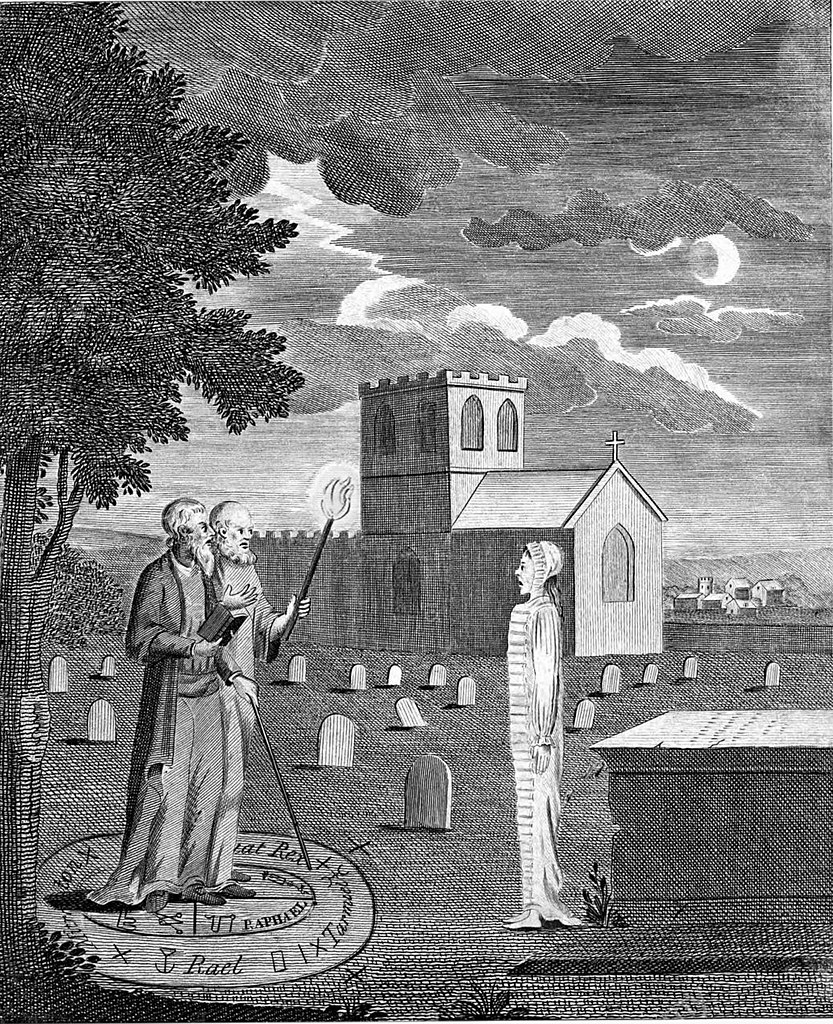

Necromancy is the practice of magic or black magic involving communication with the dead – either by summoning their spirits as apparitions, visions or raising them bodily – for the purpose of divination, imparting the means to foretell future events, discover hidden knowledge, to bring someone back from the dead, or to use the dead as a weapon. Sometimes referred to as "Death Magic", the term may also sometimes be used in a more general sense to refer to black magic or witchcraft.

Etymology

The word necromancy is adapted from Late Latin necromantia, itself borrowed from post-Classical Greek νεκρομαντεία (nekromanteía), a compound of Ancient Greek νεκρός (nekrós) 'dead body' and μαντεία (manteía) 'divination'; this compound form was first used by Origen of Alexandria in the 3rd century AD. The Classical Greek term was ἡ νέκυια (nekyia), from the episode of The Odyssey in which Odysseus visits the realm of the dead souls and νεκρομαντεία in Hellenistic Greek, rendered as necromantīa in Latin, and as necromancy in 17th-century English.

Use in antiquity

Early necromancy was related to – and most likely evolved from – shamanism, which calls upon spirits such as the ghosts of ancestors. Classical necromancers addressed the dead in "a mixture of high-pitch squeaking and low droning", comparable to the trance-state mutterings of shamans. Necromancy was prevalent throughout antiquity with records of its practice in ancient Egypt, Babylonia, Greece and Rome. In his Geographica, Strabo refers to νεκρομαντία (nekromantia), or "diviners by the dead", as the foremost practitioners of divination among the people of Persia.

Though Jewish Law prescribed the death penalty to practitioners of necromancy (Leviticus 20:27), this warning was not always heeded. One of the foremost examples is when King Saul had the Witch of Endor invoke the spirit of Samuel, a judge and prophet, from Sheol using a ritual conjuring pit (1 Samuel 28:3–25). However, the witch was shocked at the presence of the real spirit of Samuel for it says, "when the woman saw Samuel, she cried out in a loud voice." Samuel questioned his reawakening asking, "Why hast thou disquieted me?" Saul did not receive a death penalty (his being the highest authority in the land) but he did receive it from God himself as prophesied by Samuel during that conjuration – within a day he died in battle along with his son Jonathan.

Some Christian writers later rejected the idea that humans could bring back the spirits of the dead and interpreted such shades as disguised demons instead, thus conflating necromancy with demon summoning. Caesarius of Arles entreats his audience to put no stock in any demons or gods other than the Christian God, even if the working of spells appears to provide benefit. He states that demons only act with divine permission and are permitted by God to test Christian people. Caesarius does not condemn man here; he only states that the art of necromancy exists, although it is prohibited by the Bible.

In the Middle Ages

Many medieval writers believed that actual resurrection required the assistance of God. They saw the practice of necromancy as conjuring demons who took the appearance of spirits. The practice became known explicitly as maleficium, and the Catholic Church condemned it. Though the practitioners of necromancy were linked by many common threads, there is no evidence that these necromancers ever organized as a group. One noted commonality among practitioners of necromancy was usually the utilization of certain toxic and hallucinogenic plants from the nightshade family such as black henbane, jimson weed, belladonna or mandrake, usually in magic salves or potions.

Medieval necromancy is believed to be a synthesis of astral magic derived from Arabic influences and exorcism derived from Christian and Jewish teachings. Arabic influences are evident in rituals that involve moon phases, sun placement, day and time. Fumigation and the act of burying images are also found in both astral magic and necromancy. Christian and Jewish influences appear in the symbols and in the conjuration formulas used in summoning rituals.

Practitioners were often members of the Christian clergy. In some instances, mere apprentices or those ordained to lower orders dabbled in the practice. They were connected by a belief in the manipulation of spiritual beings – especially demons – and magical practices. These practitioners were almost always literate and well educated. Most possessed basic knowledge of exorcism and had access to texts of astrology and of demonology. Clerical training was informal and university-based education rare. Most were trained under apprenticeships and were expected to have a basic knowledge of Latin, ritual and doctrine. This education was not always linked to spiritual guidance and seminaries were almost non-existent. This situation allowed some aspiring clerics to combine Christian rites with occult practices despite its condemnation in Christian doctrine.

Often, accusations of necromancy were made against those accused of witchcraft. William II de Soules, known as "Bad Lord Soules," was accused of necromancy and boiled alive in oil.

Modern usage

In the present day, necromancy is more generally used as a term to describe manipulation of death and the dead, or the pretense thereof, often facilitated through the use of ritual magic or some other kind of occult ceremony. Contemporary séances, channeling and Spiritualism verge on necromancy when supposedly invoked spirits are asked to reveal future events or secret information.

Many necromancers utilize human bones, such as a skull, combined with meditation in their rituals.