Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in the impoverished districts in and around Whitechapel in the East End of London in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporary journalistic accounts, the killer was called the "Whitechapel Murderer" and "Leather Apron."

Background

Attacks ascribed to Jack the Ripper typically involved female prostitutes who lived and worked in the slums of the East End of London. Their throats were cut prior to abdominal mutilations. The removal of internal organs from at least three of the victims led to proposals that their killer had some anatomical or surgical knowledge. Rumours that the murders were connected intensified in September and October 1888, and numerous letters were received by media outlets and Scotland Yard from individuals purporting to be the murderer.

Murders

The large number of attacks against women in the East End during this time adds uncertainty to how many victims were murdered by the same individual. Eleven separate murders, stretching from 3 April 1888 to 13 February 1891, were included in a London Metropolitan Police Service investigation and were known collectively in the police docket as the "Whitechapel murders." Opinions vary as to whether these murders should be linked to the same culprit, but five of the eleven Whitechapel murders, known as the "canonical five", are widely believed to be the work of the Ripper.

The canonical five Ripper victims are Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. Mary Jane Kelly is generally considered to be the Ripper's final victim, and it is assumed that the crimes ended because of the culprit's death, imprisonment, institutionalisation, or emigration. The Whitechapel murders file details another four murders that occurred after the canonical five: those of Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie, the Pinchin Street torso, and Frances Coles.

Investigation

The vast majority of the City of London Police files relating to their investigation into the Whitechapel murders were destroyed in the Blitz. The surviving Metropolitan Police files allow a detailed view of investigative procedures in the Victorian era. A large team of policemen conducted house-to-house inquiries throughout Whitechapel. Forensic material was collected and examined. Suspects were identified, traced, and either examined more closely or eliminated from the inquiry. Modern police work follows the same pattern. More than 2,000 people were interviewed, "upwards of 300" people were investigated, and 80 people were detained. Following the murders of Stride and Eddowes, the Commissioner of the City Police, Sir James Fraser, offered a reward of £500 for the arrest of the Ripper.

Butchers, slaughterers, surgeons, and physicians were suspected because of the manner of the mutilations. A surviving note from Major Henry Smith, Acting Commissioner of the City Police, indicates that the alibis of local butchers and slaughterers were investigated, with the result that they were eliminated from the inquiry. A report from Inspector Swanson to the Home Office confirms that 76 butchers and slaughterers were visited, and that the inquiry encompassed all their employees for the previous six months.

Whitechapel Vigilance Committee

In September 1888, a group of volunteer citizens in London's East End formed the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee. They patrolled the streets looking for suspicious characters, partly because of dissatisfaction with the failure of police to apprehend the perpetrator, and also because some members were concerned that the murders were affecting businesses in the area.

Letters

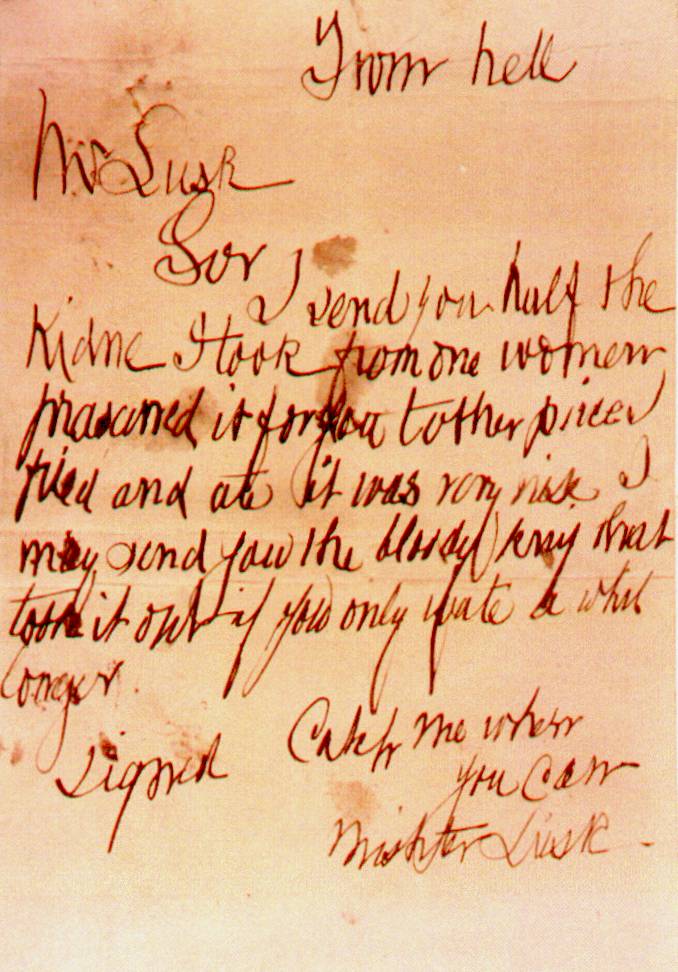

Over the course of the Whitechapel murders, the police, newspapers, and other individuals received hundreds of letters regarding the case. Some letters were well-intentioned offers of advice as to how to catch the killer, but the vast majority were either hoaxes or generally useless. Three letters in particular are prominent, and may have been written by the killer himself: the "Dear Boss" letter, the "Saucy Jacky" postcard and the "From Hell" letter.

The "Dear Boss" letter, dated 25 September and postmarked 27 September 1888, was received that day by the Central News Agency, and was forwarded to Scotland Yard on 29 September. After the publication of the "Dear Boss" letter, "Jack the Ripper" supplanted "Leather Apron" as the name adopted by the press and public to describe the killer.

The "Saucy Jacky" postcard was postmarked 1 October 1888 and was received the same day by the Central News Agency. The handwriting was similar to the "Dear Boss" letter, and mentioned the canonical murders committed on 30 September, which the author refers to by writing "double event this time".

The "From Hell" letter was received by George Lusk, leader of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, on 16 October 1888. The handwriting and style is unlike that of the "Dear Boss" letter and "Saucy Jacky" postcard. The letter came with a small box in which Lusk discovered half of a human kidney. The phrase “From Hell” was well known in Victorian London. A novel by that title, Letters From Hell, written by Danish priest Valdemar Thisted, enjoyed great popularity in Europe at that time. The plot of the novel follows a non-Christian who has died and is forced to endure the tortures of Hell.

A journalist named Fred Best reportedly confessed in 1931 that he and a colleague at The Star had written the letters signed "Jack the Ripper" to heighten interest in the murders and "keep the business alive".

Suspects

The concentration of the killings around weekends and public holidays and within a short distance of each other has indicated to many that the Ripper was in regular employment and lived locally. Others have opined that the killer was an educated upper-class man, possibly a doctor or an aristocrat who ventured into Whitechapel from a more well-to-do area. Such theories draw on cultural perceptions such as fear of the medical profession, a mistrust of modern science, or the exploitation of the poor by the rich.

After the murder of Mary Kelly, two women working nearby told police about a man they encountered who they believed should be investigated. The man was dressed like a gentleman, wearing a tall black hat and black coat. He was about five feet, six inches tall with a black mustache and carried a black case about a foot long. In both incidents, when the women asked what was in the bag, the man replied: “Something that the ladies don't like.”

There are many, varied theories about the actual identity and profession of Jack the Ripper, but authorities are not agreed upon any of them, and the number of named suspects reaches over one hundred. Despite continued interest in the case, the Ripper's identity remains unknown.

Legacy

The nature of the Ripper murders and the impoverished lifestyle of the victims drew attention to the poor living conditions in the East End and galvanised public opinion against the overcrowded, insanitary slums. In the two decades after the murders, the worst of the slums were cleared and demolished, but the streets and some buildings survive, and the legend of the Ripper is still promoted by various guided tours of the murder sites and other locations pertaining to the case.

Jack the Ripper features in hundreds of works of fiction and works which straddle the boundaries between fact and fiction, including the Ripper letters and a hoax diary. The Ripper appears in novels, short stories, poems, comic books, games, songs, plays, operas, television programmes, and films. More than 100 non-fiction works deal exclusively with the Jack the Ripper murders, making this case one of the most written-about in the true-crime genre.