Feng Shui

Feng Shui, sometimes called Chinese geomancy, is a traditional form of geomancy that originated in Ancient China and uses energy forces to harmonize individuals with their surrounding environment. The term feng shui means, literally, "wind-water" (i.e., fluid).

From ancient times, landscapes and bodies of water were thought to direct the flow of the universal Qi – "cosmic current" or energy – through places and structures. More broadly, feng shui includes astronomical, astrological, architectural, cosmological, geographical, and topographical dimensions.

History

Some of the foundations of feng shui go back more than 3,500 years before the invention of the magnetic compass, originating in Chinese astronomy. Some current techniques can be traced to Neolithic China, while others were added later.

Chinese used circumpolar stars to determine the north–south axis of settlements. This technique explains why Shang palaces at Xiaotun lie 10° east of due north. In some of the cases, they bisected the angle between the directions of the rising and setting sun to find north. This technique provided the more precise alignments of the Shang walls at Yanshi and Zhengzhou. Rituals for using a feng shui instrument required a diviner to examine current sky phenomena to set the device and adjust their position in relation to the device.

The oldest examples of instruments used for feng shui are liuren astrolabes, also known as shi. These consist of a lacquered, two-sided board with astronomical sightlines. The earliest examples of liuren astrolabes have been unearthed from tombs that date between 278 BC and 209 BC. Along with divination for Da Liu Ren the boards were commonly used to chart the motion of Taiyi (Pole star) through the nine palaces.

The magnetic compass was used for feng shui since its invention. Traditional feng shui instrumentation consists of the Luopan or the earlier south-pointing spoon, although a conventional compass could suffice if one understood the differences.A feng shui ruler (a later invention) may also be employed.

Later history

After the Song dynasty, divination began to decline as a political institution and instead became an increasingly private affair. Many feng shui experts and diviners sold their services to the public market, allowing feng shui to quickly grow in popularity.

During the Late Qing dynasty, feng shui became immensely popular. Widespread destitution and increasing government despotism led to feng shui becoming more widely practiced in rural areas. The Qing dynasty attempted to crack down on heterodoxy following the White Lotus Rebellion and Taiping Revolt, but feng shui's decentralization made it difficult to suppress in popular and elite circles.

Under China's Century of Humiliation, feng shui began to receive implicit government encouragement as a method of colonial resistance. Through the militarization of the countryside, the local gentry used feng shui to justify and promote popular attacks against missionaries and colonial infrastructure. This allowed local elites and government officials to bypass foreign extraterritoriality and maintain local sovereignty.

Following the rise of Communist China, religion and traditional cosmology were suppressed more than ever, in the name of ideological purity. Decentralized heterodoxies, like feng shui, were best adapted to survive this period. As a result, feng shui became one of the only alternative forms of thought within the Chinese countryside. Feng shui experts remained highly sought after, in spite of numerous campaigns to suppress the practice.

It was only after China's Reform and Opening-Up that feng shui would see a complete resurgence. As economic liberalization promoted social competition and individualism, feng shui was able to find new footing due to its focus on individualism and amoral justification of social differences.

Foundational concepts

Feng shui views good and bad fortune as tangible elements that can be managed through predictable and consistent rules. This involves the management of Qi, a form of cosmic energy. In situating the local environment to maximize good Qi, one can optimize their own good fortune. Feng shui holds that one's external environment can affect one's internal state. A goal of the practice is to achieve a "perfect spot," a location and an axis in time that can help one achieve harmony with the universe.

Traditional feng shui is inherently a form of ancestor worship. Popular in farming communities for centuries, it was built on the idea that the ghosts of ancestors and other independent, intangible forces, both personal and impersonal, affected the material world, and that these forces needed to be placated through rites and suitable burial places.

Bagua

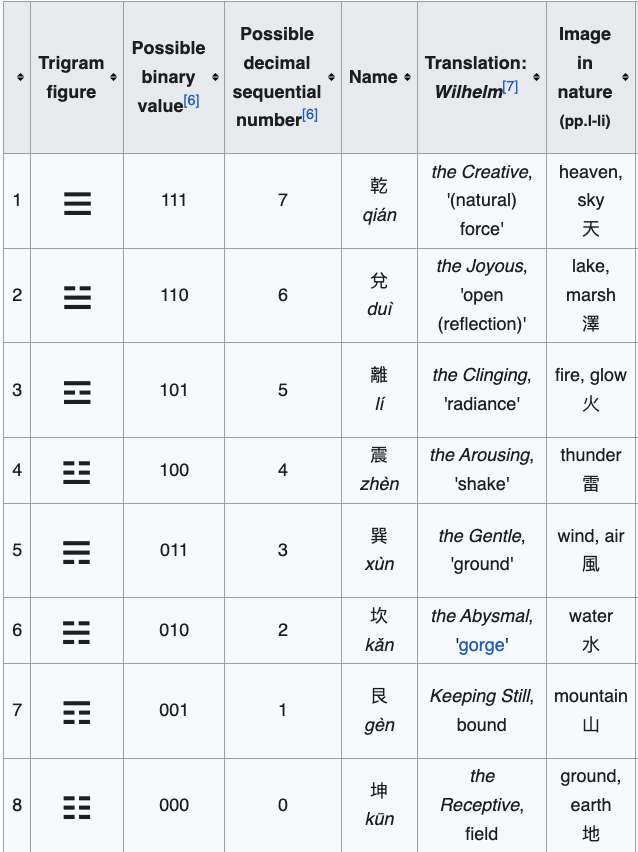

The bagua is a set of symbols from China intended to illustrate the nature of reality as being composed of mutually opposing forces reinforcing one another. Bagua is a group of trigrams—composed of three lines, each either "broken" or "unbroken," which represent yin and yang, respectively. Eight bagua predate their mentions in the I Ching.

Traditional feng shui

Traditional feng shui is an ancient system based upon the observation of heavenly time and earthly space. Literature, as well as archaeological evidence, provide some idea of the origins and nature of feng shui techniques. Aside from books, there is also a strong oral history. In many cases, masters have passed on their techniques only to selected students or relatives.

Modern practitioners of feng shui draw from several branches in their own practices.

Western feng shui

More recent forms of feng shui simplify principles that come from the traditional branches, and focus mainly on the use of the bagua.

The Eight Life Aspirations style of feng shui is a simple system which coordinates each of the eight cardinal directions with a specific life aspiration or station such as family, wealth, fame, etc., which come from the Bagua government of the eight aspirations. Life Aspirations is not otherwise a geomantic system.