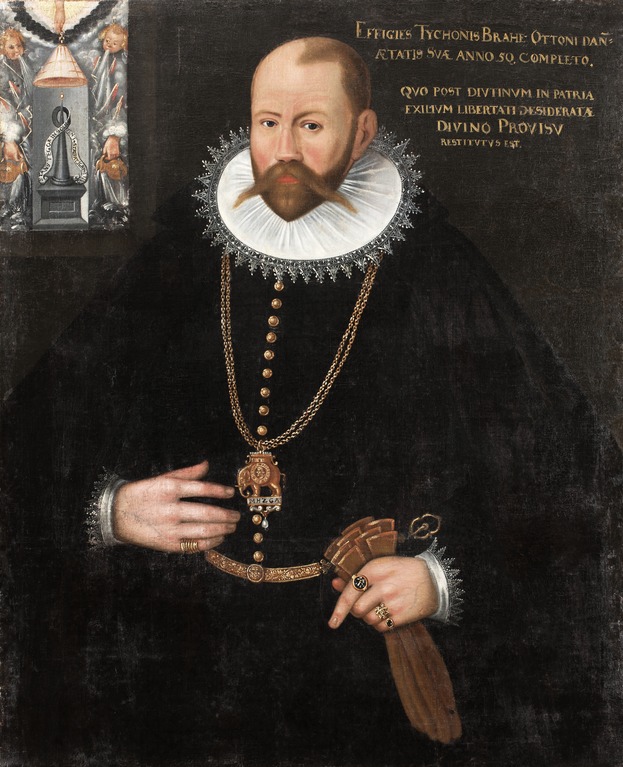

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe (14 December 1546 – 24 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was known during his lifetime as an astronomer, astrologer, and an alchemist. He was the last major astronomer before the invention of the telescope.

Early education

From ages 6 to 12, Tycho attended Latin school, probably in Nykøbing. At age 12, on 19 April 1559, Tycho began studies at the University of Copenhagen. There, following his uncle's wishes, he studied law, but also studied a variety of other subjects and became interested in astronomy. At the university, Aristotle was a staple of scientific theory, and Tycho likely received a thorough training in Aristotelian physics and cosmology. He experienced the solar eclipse of 21 August 1560, and was greatly impressed by the fact that it had been predicted, although the prediction based on current observational data was a day off. He realized that more accurate observations would be the key to making more exact predictions. He purchased an ephemeris and books on astronomy, including Johannes de Sacrobosco's De sphaera mundi, Petrus Apianus's Cosmographia seu descriptio totius orbis and Regiomontanus's De triangulis omnimodis.

Jørgen Thygesen Brahe, however, wanted Tycho to educate himself in order to become a civil servant, and sent him on a study tour of Europe in early 1562. 15-year old Tycho was given as mentor the 19-year-old Anders Sørensen Vedel, whom he eventually talked into allowing the pursuit of astronomy during the tour. Vedel and his pupil left Copenhagen in February 1562. On 24 March, they arrived in Leipzig, where they matriculated at the Lutheran Leipzig University.

Pursuit of astronomy

In 1563, he observed a close conjunction of the planets Jupiter and Saturn, and noticed that the Copernican and Ptolemaic tables used to predict the conjunction were inaccurate. This led him to realise that progress in astronomy required systematic, rigorous observation, night after night, using the most accurate instruments obtainable. He began maintaining detailed journals of all his astronomical observations. In this period, he combined the study of astronomy with astrology, laying down horoscopes for different famous personalities.

In 1566, Tycho left to study at the University of Rostock. Here, he studied with professors of medicine at the university's famous medical school and became interested in medical alchemy and herbal medicine.

In April 1567, Tycho returned home from his travels, with a firm intention of becoming an astrologer. Although he had been expected to go into politics and the law, like most of his kinsmen, and although Denmark was still at war with Sweden, his family supported his decision to dedicate himself to the sciences. His father wanted him to take up law, but Tycho was allowed to travel to Rostock and then to Augsburg (where he built a great quadrant), Basel, and Freiburg. In 1568, he was appointed a canon at the Cathedral of Roskilde, a largely honorary position that would allow him to focus on his studies. At the end of 1570, he was informed of his father's ill health, so he returned to Knutstorp Castle, where his father died on 9 May 1571. The war was over, and the Danish lords soon returned to prosperity. Soon, another uncle, Steen Bille, helped him build an observatory and alchemical laboratory at Herrevad Abbey. Tycho was acknowledged by King Frederick II who proposed to him that an observatory be built to better study the night sky. After accepting this proposal, the location for the Uraniborg's construction took place at a remote island called Hven in the Sont near Copenhagen, the earliest large observatory in Christian Europe.

1572 supernova

On 11 November 1572, Tycho observed (from Herrevad Abbey) a very bright star, now numbered SN 1572, which had unexpectedly appeared in the constellation Cassiopeia. Because it had been maintained since antiquity that the world beyond the Moon's orbit was eternally unchangeable (celestial immutability was a fundamental axiom of the Aristotelian world-view), other observers held that the phenomenon was something in the terrestrial sphere below the Moon. However, Tycho observed that the object showed no daily parallax against the background of the fixed stars. This implied that it was at least farther away than the Moon and those planets that do show such parallax. He also found that the object did not change its position relative to the fixed stars over several months, as all planets did in their periodic orbital motions, even the outer planets, for which no daily parallax was detectable. This suggested that it was not even a planet, but a fixed star in the stellar sphere beyond all the planets.

In 1573, he published a small book De nova stella, thereby coining the term nova for a "new" star (we now classify this star as a supernova and know that it is 7,500 light-years from Earth). This discovery was decisive for his choice of astronomy as a profession. Tycho was strongly critical of those who dismissed the implications of the astronomical appearance, writing in the preface to De nova stella: "O crassa ingenia. O caecos coeli spectatores" ("Oh thick wits. Oh blind watchers of the sky"). The publication of his discovery made him a well-known name among scientists in Europe.

Lord of Hven

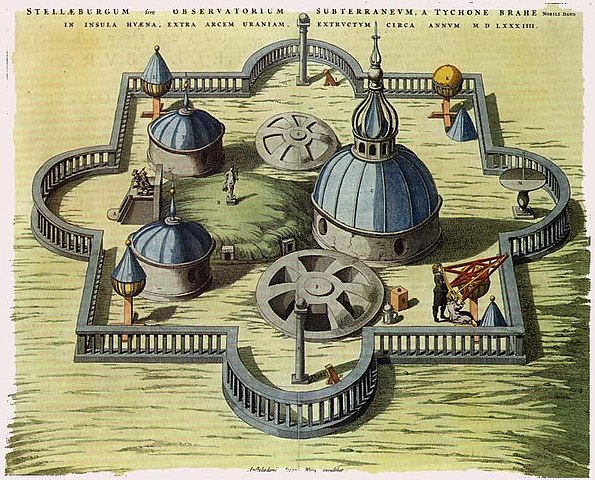

In 1576, King Frederick offered Tycho the island of Hven in Øresund and funding to set up an observatory. Tycho took control of agricultural planning, requiring the peasants to cultivate twice as much as they had done before, and he also exacted corvée labor from the peasants for the construction of his new castle. He envisioned his castle Uraniborg as a temple dedicated to the muses of arts and sciences, rather than as a military fortress; indeed, it was named after Urania, the muse of astronomy.

When Tycho realized that the towers of Uraniborg were not adequate as observatories because of the instruments' exposure to the elements and the movement of the building, he constructed an underground observatory close to Uraniborg called Stjerneborg (Star Castle) in 1584. This consisted of several hemispherical crypts which contained the great equatorial armillary, large azimuth quadrant, zodiacal armillary, largest azimuth quadrant of steel and the trigonal sextant.

The basement of Uraniborg included an alchemical laboratory with 16 furnaces for conducting distillations and other chemical experiments. Unusually for the time, Tycho established Uraniborg as a research centre, where almost 100 students and artisans worked from 1576 to 1597. Uraniborg also contained a printing press and a paper mill, both among the first in Scandinavia, enabling Tycho to publish his own manuscripts, on locally made paper with his own watermark.

As part of Tycho's duties to the Crown in exchange for his estate, he fulfilled the functions of a royal astrologer. At the beginning of each year, he had to present an Almanac to the court, predicting the influence of the stars on the political and economic prospects of the year. And at the birth of each prince, he prepared their horoscopes, predicting their fates.

Exile

When King Frederick died in 1588, his son and heir Christian IV was only 11 years old. A regency council was appointed to rule for the young prince-elect until his coronation in 1596. The head of the council (Steward of the Realm) was Christoffer Valkendorff, who disliked Tycho after a conflict between them, and hence Tycho's influence at the Danish court steadily declined.

Feeling that his legacy on Hven was in peril, he approached the Dowager Queen Sophie and asked her to affirm in writing her late husband's promise to endow Hven to Tycho's heirs. King Christian IV followed a policy of curbing the power of the nobility by confiscating their estates to minimize their income bases, by accusing nobles of misusing their offices and of heresies against the Lutheran church. Tycho, who was known to sympathize with the Philippists (followers of Philip Melanchthon), was among the nobles who fell out of grace with the new king. The king's doctor Peter Severinus, who also had personal gripes with Tycho, and several gnesio-Lutheran Bishops who suspected Tycho of heresy—a suspicion motivated by his known Philippist sympathies, his pursuits in medicine and alchemy (both of which he practiced without the church's approval) and his prohibiting the local priest on Hven to include the exorcism in the baptismal ritual.

Tycho left Hven in 1597, bringing some of his instruments with him to Copenhagen, and entrusting others to a caretaker on the island. Shortly before leaving, he completed his star catalogue giving the positions of 1,000 stars. After some unsuccessful attempts at influencing the king to let him return; including showcasing his instruments on the wall of the city, he finally acquiesced to exile.

Death

Tycho suddenly contracted a bladder or kidney ailment after attending a banquet in Prague, and died eleven days later, on 24 October 1601, at the age of 54. According to Kepler's first-hand account, Tycho had refused to leave the banquet to relieve himself because it would have been a breach of etiquette. After he returned home, he was no longer able to urinate, except eventually in very small quantities and with excruciating pain. The night before he died, he suffered from a delirium during which he was frequently heard to exclaim that he hoped he would not seem to have lived in vain.

Investigations in the 1990s suggested that Tycho may not have died from urinary problems, but instead from mercury poisoning. It was speculated that he had been intentionally poisoned. The two main suspects were his assistant, Johannes Kepler, whose motives would be to gain access to Tycho's laboratory and chemicals, and his cousin, Erik Brahe, at the order of friend-turned-enemy Christian IV, because of rumors that Tycho had had an affair with Christian's mother.

Tycho is buried in the Church of Our Lady before Týn, in Old Town Square near the Prague Astronomical Clock.

Tycho's observational astronomy

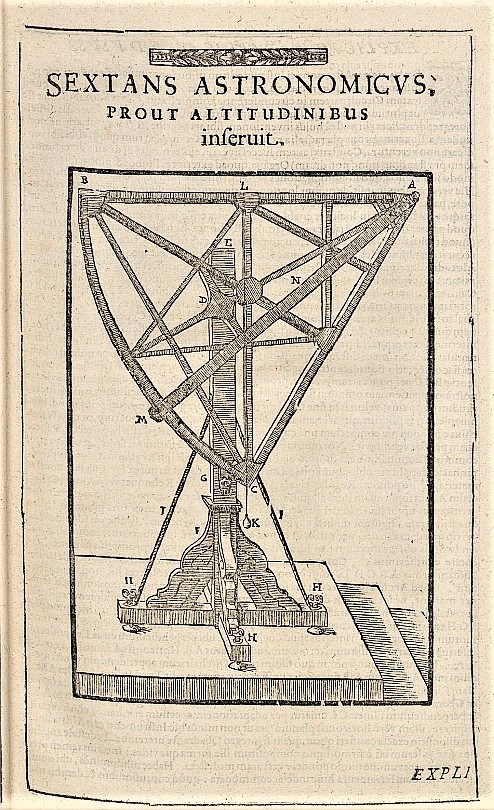

Tycho's view of science was driven by his passion for accurate observations, and the quest for improved instruments of measurement drove his life's work. Tycho was the last major astronomer to work without the aid of a telescope, soon to be turned skyward by Galileo Galilei and others. Given the limitations of the naked eye for making accurate observations, he devoted many of his efforts to improving the accuracy of the existing types of instrument—the sextant and the quadrant. He designed larger versions of these instruments, which allowed him to achieve much higher accuracy. Because of the accuracy of his instruments, he quickly realized the influence of wind and the movement of buildings, and instead opted to mount his instruments underground directly on the bedrock.

Tycho's observations of stellar and planetary positions were noteworthy both for their accuracy and quantity. With an accuracy approaching one arcminute, his celestial positions were much more accurate than those of any predecessor or contemporary—about five times as accurate as the observations of Wilhelm of Hesse.

He has been alleged to be the author or co-author of the Magical Calendar (Calendarium Naturale Magicum Perpetuum), an important early work of astrological and Kabbalistic magic.