Ley line

Ley lines (/leɪˈlaɪnz/) are straight alignments drawn between various historic structures, prehistoric sites and prominent landmarks. The idea was first developed in early 20th-century Europe, with ley line believers arguing that these alignments were recognised by ancient societies that deliberately erected structures along them. They are considered a form of topographical geomancy.

Archaeologists and scientists regard ley lines as an example of pseudoarchaeology and pseudoscience.

Early theories

The idea that ancient sacred sites might have been constructed in alignment with one another was first proposed in 1846 by the Reverend Edward Duke, who observed that some prehistoric monuments and medieval churches aligned with each other.

In 1909, the idea was advanced in Germany. There, Wilhelm Teudt had argued for the presence of linear alignments connecting various sites but suggested that they had a religious and astronomical function. In Germany, the idea was referred to as Heilige Linien ('holy lines'), an idea adopted by some proponents of Nazism.

Alfred Watkins' theory

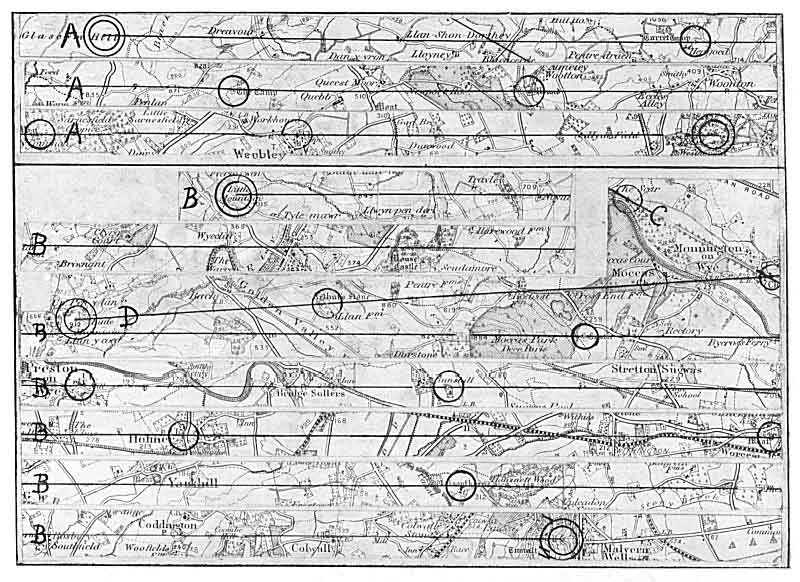

The idea of "leys" as paths traversing the British landscape was developed by Alfred Watkins, a wealthy businessman and antiquarian who lived in Hereford. According to his account, he was driving across the hills near Blackwardine, Herefordshire, when he looked across the landscape and observed the way that several features lined up together. He subsequently began drawing lines across his Ordnance Survey maps, developing the view that ancient British people had tended to travel in straight lines, using "mark points" along the landscape to guide them.

He put forward his idea of ley lines in the 1922 book Early British Trackways and then again, in greater depth, in the 1925 book The Old Straight Track. He proposed the existence of a network of completely straight roads that cut through a range of prehistoric, Roman, and medieval structures. In his view, these straight tracks were ancient trade routes.

Watkins referred to these lines as "leys" although had reservations about doing so. The term ley derived from the Old English term for a cleared space, with Watkins adopting it for his lines because he found it to be part of the place-names of various settlements that were along the lines he traced. He also observed the recurrence of "cole" and "dod" in English place-names, thus suggesting that the individuals who established these lines were referred to as a "coleman" or "dodman."

Watkins believed that the Long Man of Wilmington in Sussex depicted a prehistoric "dodman" with his equipment for determining a ley line. His ideas were rejected by most experts on British prehistory at the time. His critics noted that the straight lines he proposed would have been highly impractical means of crossing hilly or mountainous terrain, and that many of the sites he selected as evidence for the leys were of disparate historical origins. Some of Watkins' other ideas, such as his belief that widespread forest clearance took place in prehistory rather than later, would nevertheless later be recognised by archaeologists.

Straight Track Club

In 1926, advocates of Watkins' beliefs established the Straight Track Club. To assist this growing body of enthusiasts who were looking for their own ley lines in the landscape, in 1927, Watkins published The Ley Hunter's Manual.

Proponents of Watkins' ideas sent in letters to the archaeologist O. G. S. Crawford, then editor of the Antiquity journal. Crawford filed these letters under a section of his archive titled "Crankeries" and was annoyed that educated people believed such ideas when they were demonstrably incorrect. He refused to publish an advert for The Old Straight Track in Antiquity, at which Watkins became very bitter towards him.

Watkins' last book, Archaic Tracks Around Cambridge, was published in 1932. Watkins died on 7 April 1935. The Club survived him, although it became largely inactive at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 and formally disbanded in 1948. The archaeoastronomer Clive Ruggles noted that after the 1920s, "ley lines soon faded into obscurity." The historian Ronald Hutton similarly noted that there had been a "virtual demise" in the idea by the 1950s, in part due to "a natural weariness with a spent enthusiasm."

Earth Mysteries movement

From the 1940s through to the 1960s, a belief in ley lines was taken up by members of the counterculture, where—in the words of the archaeologist Matthew Johnson—they were attributed with "sacred significance or mystical power." Ruggles noted that in this period, ley lines came to be conceived as "lines of power, the paths of some form of spiritual force or energy accessible to our ancient ancestors but now lost to narrow-minded twentieth-century scientific thought."

In his 1961 book Skyways and Landmarks, Tony Wedd published his idea that Watkins' leys were both real and served as ancient markers to guide alien spacecraft that were visiting Earth. He came to this conclusion after comparing Watkins' ideas with those of the French ufologist Aimé Michel, who argued for the existence of "orthotenies," lines along which alien spacecraft travelled. Wedd suggested that either spacecraft were following the prehistoric landmarks for guidance or that both the leys and the spacecraft were following a "magnetic current" flowing across the Earth.

Wedd's ideas were taken up by the writer John Michell, who promoted them to a wider audience in his 1967 book The Flying Saucer Vision. In this book, Michell promoted the ancient astronaut belief that extraterrestrials had assisted humanity during prehistory, when humans had worshipped these entities as gods, but that the aliens left when humanity became too materialistic and technology-focused. He also argued that humanity's materialism was driving it to self-destruction, but that this could be prevented by re-activating the ancient centres which would facilitate renewed contact with the aliens.

The ley hunting community

In 1962, a group of ufologists established the Ley Hunter's Club. Parish churches were particularly favoured by the ley hunters, who often worked on the assumption that such churches had almost always been built atop pre-Christian sacred sites. The 1970s and 1980s also saw the increase in publications on the topic of ley lines. One ley lines enthusiast, Philip Heselton, established the Ley Hunter magazine, which was launched in 1965.

Part of the popularity of ley hunting was that individuals without any form of professional training in archaeology could take part and feel that they could rediscover "the magical landscapes of the past." Ley hunting welcomed those who had "a strong interest in the past but feel excluded from the narrow confines of orthodox academia." The ley hunting movement often blended their activities with other esoteric practices, such as numerology and dowsing.

Dragon Project

Paul Devereux was one of the founding members of the Dragon Project, launched in London in 1977 with the purpose of conducting radioactivity and ultrasonic tests at prehistoric sites, particularly the stone circles created in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. The Dragon Project continued its research throughout the 1980s, finding that certain prehistoric sites did show higher or lower than average rates of radiation but that others did not and that there was no consistent pattern.

During the 1980s, professional archaeologists in Britain began to engage with the ley hunting movement. In 1983, Ley Lines in Question, a book written by the archaeologists Tom Williamson and Liz Bellamy, was published. They highlighted that the British landscape was so highly covered in historic monuments that it was statistically unlikely that any straight line could be drawn across the landscape without passing through several such sites. They also demonstrated that ley hunters had often said that certain markers were Neolithic, and thus roughly contemporary with each other, when often they were of widely different dates, such as being Iron Age or medieval.

Schism in the community

From one perspective, the tale of ley-hunting is one of a classic modern religious movement, arising with an apocalyptic language which appropriated some of the tropes of evangelical Christianity, flourished for a brief time, and then subsided into a set of motifs and assumptions retained by a particular subculture of believers.

From another, it is a frustrating tale of missed opportunities. The neglect of landscape and sensory experience by mainstream archaeology in the mid twentieth century was a serious omission, which earth mysteries researchers could remedy to the lasting benefit of human knowledge. Misled by a fixed and dogmatic set of ideas, however, they passed this by to focus on an attempted proof of beliefs which were ultimately based on faith alone.

The Ley Hunter magazine ceased publication in 1999. Its last editor, Danny Sullivan, stated that the idea of leys was "dead." Hutton suggested that some of the enthusiasm formerly directed toward leys was instead directed toward archaeo-astronomy.

Modern practices

Belief in ley lines persists among various esoteric groups, having become an enduring feature of some brands of esotericism. As Hutton observed, beliefs in "ancient earth energies have passed so far into the religious experience of the New Age counter-culture of Europe and America that it is unlikely that any tests of evidence would bring about an end to belief in them."

During the 1970s and 1980s, a belief in ley lines fed into the modern Pagan community. Research that took place in 2014 for instance found that various modern Druids and other Pagans believed that there were ley lines focusing on the Early Neolithic site of Coldrum Long Barrow in Kent, southeast England.

In the US city of Seattle a dowsing organisation called the Geo Group plotted what they believed were the ley lines across the city. They stated that their "project made Seattle the first city on Earth to balance and tune its ley-line system." The Seattle Arts Commission contributed $5,000 to the project, bringing criticisms from members of the public who regarded it as a waste of money.

Some occultists believe that ley lines are a form of topographical geomancy and may be used for purposes of divination in a similar fashion to geographic songlines used by aboriginal Australians.

Scientific criticism

Ley lines have been characterised by mainstream scientists as a form of pseudoscience.

Statistical significance tests have shown that supposed ley-line alignments are no more significant than random occurrences and/or have been generated by selection effects. The paper by statistician Simon Broadbent is one such example and the discussion after the article involving a large number of other statisticians demonstrates the high level of agreement that alignments have no significance compared to the null hypothesis of random locations.

A study by David George Kendall used the techniques of shape analysis to examine the triangles formed by standing stones to deduce if these were often arranged in straight lines. The shape of a triangle can be represented as a point on the sphere, and the distribution of all shapes can be thought of as a distribution over the sphere. The sample distribution from the standing stones was compared with the theoretical distribution to show that the occurrence of straight lines was no more than average.

The archaeologist Richard Atkinson once demonstrated this by taking the positions of telephone booths and pointing out the existence of "telephone box leys". This, he argued, showed that the mere existence of such lines in a set of points does not prove that the lines are deliberate artefacts, especially since it is known that telephone boxes were not laid out in any such manner or with any such intention.