Christianity

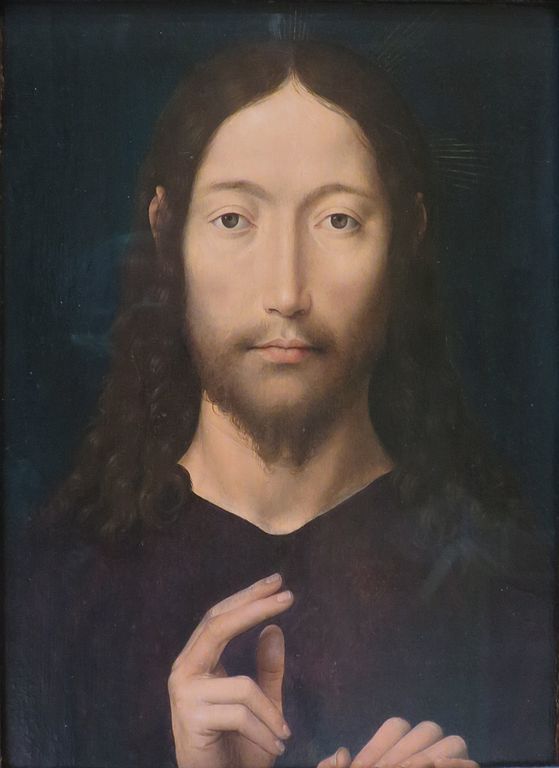

Christianity is an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest religion, with about 2.5 billion followers. Its adherents, known as Christians, make up a majority of the population in 157 countries and territories, and believe that Jesus is the Christ, whose coming as the Messiah was prophesied in the Hebrew Bible (called the Old Testament in Christianity) and chronicled in the New Testament.

Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches, as well as in its doctrines concerning justification and the nature of salvation, ecclesiology, ordination, and Christology.

Fundamental tenants

A foundational belief among various Christian denominations is that Jesus was the Son of God, incarnated on earth, who ministered, suffered, and died on a cross, but later rose from the dead for the salvation of all humanity.

The primary holy text of Christianity is referred to as the Bible's "New Testament." This book describes Jesus' life and teachings in the four canonical gospels ("good news") of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Additionally, the Old Testament is revered as the gospel's historical background which foretold the coming of Jesus Christ.

Etymology

Early Jewish Christians referred to themselves as "The Way" (Koinē Greek: τῆς ὁδοῦ), probably coming from Isaiah 40:3, "prepare the way of the Lord."

According to Acts 11:26, the term "Christian" (Χρῑστῐᾱνός, Khrīstiānós), meaning "followers of Christ" in reference to Jesus's disciples, was first used in the city of Antioch by the non-Jewish inhabitants there. The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity/Christianism" (Χρῑστῐᾱνισμός, Khrīstiānismós) was by Ignatius of Antioch around 100 AD.

Early history

Christianity began as a Second Temple Judaic sect in the 1st century in the Roman province of Judea. Jesus' apostles and their followers spread around the Levant, Europe, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Transcaucasia, Egypt, and Ethiopia, despite initial persecution. It soon attracted gentile God-fearers, which led to a departure from Jewish customs, and, after the Fall of Jerusalem, AD 70 which ended the Temple-based Judaism, Christianity slowly separated from Judaism.

Persecution of Christians occurred intermittently and on a small scale by both Jewish and Roman authorities, with Roman action starting at the time of the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. Examples of early executions under Jewish authority reported in the New Testament include the deaths of Saint Stephen and James. The Decian persecution was the first empire-wide conflict, when the edict of Decius in 250 AD required everyone in the Roman Empire (except Jews) to perform a sacrifice to the Roman gods. The Diocletianic Persecution beginning in 303 AD was also particularly severe. Roman persecution ended in 313 AD with the Edict of Milan.

While Proto-orthodox Christianity was becoming dominant, heterodox sects also existed at the same time, which held radically different beliefs. Gnostic Christianity developed a duotheistic doctrine based on illusion and enlightenment rather than forgiveness of sin. With only a few scriptures overlapping with the developing orthodox canon, most Gnostic texts and Gnostic gospels were eventually considered heretical and suppressed by mainstream Christians.

Emperor Constantine the Great decriminalized Christianity in the Roman Empire by the Edict of Milan (313), later convening the Council of Nicaea (325) where Early Christianity was consolidated into what would become the State church of the Roman Empire (380). The early history of Christianity's united church before major schisms is sometimes referred to as the "Great Church" headed by a Pope elected from among the regional church leaders.

First schisms

The Church of the East split after the Council of Ephesus (431) and Oriental Orthodoxy split after the Council of Chalcedon (451) over differences in Christology, while the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church separated in the East–West Schism (1054), especially over the authority of the bishop of Rome.

Medieval and Renaissance Periods

With the decline and fall of the Roman Empire in the West, the papacy became a political player, entering into a long period of missionary activity and expansion among pagan tribes.

In the West, from the 11th century onward, some older cathedral schools became universities. Previously, higher education had been the domain of Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools. These new universities expanded the curriculum to include academic programs for clerics, lawyers, civil servants, and physicians.

Accompanying the rise of the "new towns" throughout Europe, mendicant orders were founded, bringing the consecrated religious life out of the monastery and into the new urban setting. In this period, church building and ecclesiastical architecture reached new heights, culminating in the orders of Romanesque and Gothic architecture and the building of the great European cathedrals.

Crusades

Christian nationalism emerged during this era in which Christians felt the desire to recover lands in which Christianity had historically flourished. From 1095 under the pontificate of Urban II, the First Crusade was launched. These were a series of military campaigns in the Holy Land and elsewhere, initiated in response to pleas from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I for aid against Turkish expansion. The Crusades ultimately failed to stifle Islamic aggression and even contributed to Christian enmity with the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.

Beginning around 1184, following the crusade against Cathar heresy, various institutions, broadly referred to as the Inquisition, were established with the aim of suppressing heresy and securing religious and doctrinal unity within Christianity through conversion and prosecution.

Reformation and further schisms

The 15th-century Renaissance brought about a renewed interest in ancient and classical learning. During the Reformation, Martin Luther posted the Ninety-five Theses 1517 against the sale of indulgences. Printed copies soon spread throughout Europe. In 1521 the Edict of Worms condemned and excommunicated Luther and his followers, resulting in the schism of the Western Christendom into several branches.

Other reformers further criticized Catholic teaching and worship. These challenges developed into the movement called Protestantism, which repudiated the primacy of the pope, the role of tradition, the seven sacraments, and other doctrines and practices. The Reformation in England began in 1534, when King Henry VIII had himself declared head of the Church of England.

Throughout Europe, the division caused by the Reformation led to outbreaks of religious violence and the establishment of separate state churches in Europe. Lutheranism spread into the northern, central, and eastern parts of present-day Germany, Livonia, and Scandinavia. Calvinism and its varieties, such as Presbyterianism, were introduced in Scotland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Switzerland, and France.

Spread to the New World

Meanwhile, the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492 brought about a new wave of missionary activity. Partly from missionary zeal, but under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The expansion of the Catholic Portuguese Empire and Spanish Empire with a significant role played by the Roman Catholic Church led to the Christianization of the indigenous populations of the Americas such as the Aztecs and Incas.

Resistance to complete conversion led to the creation of many African diaspora religions in South and Central America.

Age of Enlightenment

In the era known as the Great Divergence, when in the West, the Age of Enlightenment and the scientific revolution brought about great societal changes, Christianity was confronted with various forms of skepticism and with certain modern political ideologies, such as versions of socialism and liberalism.

Some scholars and historians attribute Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution. Many well-known historical figures who influenced Western science considered themselves Christian such as Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton.

Puritan movement

The early Puritan movement (late 16th century-17th century) was Reformed or Calvinist and was a movement for reform in the Church of England. Its origins lay in the discontent with the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. The desire was for the Church of England to resemble more closely the Protestant churches of Europe, especially Geneva.

The Puritans objected to ornaments and ritual in the churches as idolatrous (vestments, surplices, organs, genuflection), which they castigated as "popish pomp and rags." They also objected to ecclesiastical courts. They refused to endorse completely all of the ritual directions and formulas of the Book of Common Prayer; the imposition of its liturgical order by legal force and inspection sharpened Puritanism into an opposition movement.

The most famous and well-known emigration to America was the migration of the Puritans, or pilgrims, left England with hopes of establishing a Puritan utopia, in the English colonies of New England, which later became the United States.

Revivalism

Revivalism refers to the Calvinist and Wesleyan revival, called the "Great Awakening," in North America which saw the development of evangelical Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Baptist, and new Methodist churches. The First Great Awakening was a wave of religious enthusiasm among Protestants in the American colonies c. 1730–1740, emphasising the traditional Reformed virtues of Godly preaching, rudimentary liturgy, and a deep sense of personal guilt and redemption by Jesus Christ.

Modern Period

Christianity in the 20th century was characterized by an accelerating secularization of Western society, which had begun in the 19th century, and by the spread of Christianity to non-Western regions of the world. The "secularization of society," attributed to the time of the Enlightenment and its following years, is largely responsible for the spread of secularism.

Vatican II

A major event of the Second Vatican Council, known as Vatican II, was the issuance by Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras of a joint expression of regret for many of the past actions that had led up to the Great Schism between the Western and Eastern churches, expressed as the Catholic-Orthodox Joint declaration of 1965. At the same time, they lifted the mutual excommunications dating from the 11th century.

Intended as a continuation of Vatican I, under Pope John XXIII the council developed into an engine of modernisation. It was tasked with making the historical teachings of the Church clear to a modern world and made pronouncements on topics including the nature of the church, the mission of the laity and religious freedom.

Rise of Fundamentalism

In the 1920s, Christian fundamentalists differed on how to understand the account of creation in Genesis, but they agreed that God was the author of creation and that humans were distinct creatures, separate from animals, and made in the image of God. While some of them advocated the belief in Old Earth creationism and a few advocated the belief in evolutionary creation, others advocated Young Earth Creationism and associated evolution with last-days atheism.

These "strident fundamentalists" in the 1920s devoted themselves to fighting against the teaching of evolution in the nation's schools and colleges, especially by passing state laws that affected public schools. In the half century after the 1925 Scopes Trial, fundamentalists had little success in shaping government policy, and they were generally defeated in their efforts to reshape the mainline denominations, which refused to join fundamentalist attacks on evolution. After Scopes was convicted, creationists throughout the United States sought similar anti-evolution laws for their states.

The original fundamentalist movement divided along clearly defined lines within conservative evangelical Protestantism as issues progressed. The broader term "evangelical" includes fundamentalists as well as people with similar religious beliefs who do not actively fight to establish theocratic laws.

A former president of the Southern Baptist Convention's Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, Richard Land, identifies fundamentalism as "far more a psychology than a theology," with three key traits shared by competing Christian theologies and even competing religions such as Islamic fundamentalists:

- certainty (of a mind unclouded by doubt)

- ferocity (against perceived enemies of their religion)

- solidarity (of "comrades in the foxhole")

Denominations

A Christian denomination is a distinct religious body within Christianity, identified by traits such as a name, organization and doctrine. Divisions between one denomination and another are primarily defined by authority and doctrine. Issues regarding the nature of Jesus, Trinitarianism, salvation, the authority of apostolic succession, and papal supremacy among others may separate one denomination from another.

There is no official recognition in most parts of the world for religious bodies, and there is no official clearinghouse which could determine the status or respectability of religious bodies. Often there is considerable disagreement between various groups about whether others should be labeled with pejorative terms such as "cult," or about whether any particular group enjoys some measure of respectability.

Globally, there are hundreds (possibly more than 1,000, depending on the precise definition of a "denomination") different Christian denominations, not including African diaspora religions such as Candomblé or Santería which incorporate many core elements of Christianity into their beliefs while rejecting other aspects.

Based on fundamental beliefs and practices, all Christian denominations can be generalized into four main groups:

- Catholic (48.6%)

- Protestant (39.8%)

- Orthodox (11%)

- Other (.5%)

Criticisms

In the 2nd century, Christianity was criticized by the Jews on various grounds, predominantly:

- that the prophecies of the Hebrew Bible could not have been fulfilled by Jesus, given that he did not have a successful life

- a sacrifice to remove sins in advance, for everyone or as a human being, did not fit the Jewish sacrifice ritual

- God in Judaism is said to judge people on their deeds instead of their beliefs.

One of the first comprehensive attacks on Christianity came from the Greek philosopher Celsus, who wrote The True Word, a polemic criticizing Christians as being unprofitable members of society.

Criticism of Christianity by other Abrahamic religions continues to the modern era: Jewish and Muslim theologians criticize the doctrine of the Trinity held by most Christians, stating that this doctrine in effect assumes that there are three gods, running against the basic tenet of monotheism.

Christian fundamentalists' literal interpretation of the Bible has been criticized by practitioners of biblical criticism for failing to take into account the circumstances in which the Christian Bible was written. Critics claim that this "literal interpretation" is not in keeping with the message which the scripture intended to convey when it was written, and it also uses the Bible for political purposes by presenting God more as a God of judgement and punishment than as a God of love and mercy.

Acceptance of slavery

The Church initially accepted slavery as part of the Greco-Roman social fabric of society, campaigning primarily for humane treatment of slaves but also admonishing slaves to behave appropriately towards their masters. During the early medieval period, Christians tolerated enslavement of non-Christians, however, following the discovery of the New World, this distinction changed to one of race rather than religion.

Nearly all Christian leaders before the late 15th century recognised the institution of slavery, within specific Biblical limitations, as being consistent with Christian theology.

Early American Christians utilized the Bible's acceptance of slavery to condone the institution of slavery in the United States. By the 1830s, tensions had begun to mount between northern and southern Baptist churches. The support of Baptists in the South for slavery can be ascribed to economic and social reasons, although this was never admitted. Instead, it was claimed that slavery was beneficent, and endorsed in the Bible by God. However, Baptists in the North disagreed strongly, claiming that God would not "condone treating one race as superior to another."

Religion of violence

Throughout history, many Christian churches have acted in opposition to the teachings of Jesus Christ by engaging in campaigns of systematic violence. Christian sects have a long tradition of using violence to persecute and murder anyone who is not willing to convert to their specific belief system, or who practices Christianity (or other religions) in a way which does not meet their approval.

The Biblical account of Joshua and the Battle of Jericho was used to justify genocide against Catholics by Oliver Cromwell. Perhaps the most poignant example of this occurred during the campaign to eliminate the Cathars, when soldiers asked Abbe Arnaud Amalric how to differentiate between heretics and the ordinary public, he replied: "Kill them all, God will recognize his own!"

Some of the most heinous period of extreme Christian violence have been:

- The Crusades (1095 to 1291): resulting in 1.7 million deaths.

- The Inquisition (1184 to 1834): resulting in 6,000 - 150,000 executions for heresy.

- European Wars of Religion (1524 - 1648): resulting in 600,000 deaths.

- European and American Witch-hunts (1450 to 1750): resulting in 30,000 - 50,000 executions for witchcraft.

Also, the widespread existence of Christian terrorist groups is an indicator that the tenants of Christianity promote violence rather than condemn it. Christian terrorist groups include paramilitary organizations, cults, and loose groups of people that might come together in order to attempt to terrorize other groups. There is also a long history of individuals being inspired to commit acts of terror due to their belief in Christianity. This is especially prominent in attacks against Jews, Muslims, members of the LGBT community, and abortion service providers.

Some of the most prolific Christian terrorist groups include:

- Ku Klux Klan: Pro-Protestant, anti-semitic, anti-Catholic, and white nationalist group in the United States

- Army of God: Anti-abortion group in the United States

- Lord's Resistance Army: Pro-Christian rebel group in Uganda

Finally, many groups espousing Christianity as their primary doctrine, characterized as cults, have engaged in criminal activity and utilized the Bible and Christian teachings to justify their illegal acts:

- Branch Davidians - Christian cult based in Waco, Texas whose members perished in a confrontation with the DEA

- Order of the Solar Temple - Christian cult whose members committed mass suicide

- Peoples Temple - Christian cult who members committed mass suicide

- The Family International - Christian cult whose members practice prostitution and sex with children

- Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS) - A Mormon offshoot cult which practices polygamy

Influence

Christianity has been intricately intertwined with the history and formation of Western society. Throughout its long history, the Church has been a major source of social services like schooling and medical care; an inspiration for art, culture and philosophy; and an influential player in politics and religion. In various ways it has sought to affect Western attitudes towards vice and virtue in diverse fields.

Festivals like Easter and Christmas are marked as public holidays; the Gregorian calendar has been adopted internationally as the civil calendar; and the calendar itself is measured from an estimation of the date of Jesus's birth.