Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek τὰ βιβλία, tà biblía, "the books") is a collection of religious texts or scriptures sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other faiths. It appears in the form of an anthology, a compilation of texts of a variety of forms, originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. These texts include theologically-focused narratives, hymns, prayers, proverbs, parables, didactic letters, admonitions, poetry, and prophecies. The collection of materials that are accepted as part of the Bible by a particular religious tradition or community is called a biblical canon. Believers generally consider the Bible to be a product of divine inspiration while understanding what that means in different ways.

With estimated total sales of over five billion copies, the Bible is widely considered to be the best-selling book of all time. It has had a profound direct influence on Western culture and history. The study of the Bible through biblical criticism has indirectly impacted culture and history as well. The Bible is currently translated or being translated into about half of the world's languages.

Origins

The origins of the oldest writings of the Israelites are lost in antiquity. The Dead Sea scrolls are dated, approximately, from 250 BCE to 100 CE, and they are the oldest existing copies of the books of the Hebrew Bible of any length. The Qumran scrolls attest to different biblical text types. In addition to the Qumran scrolls, there are three major manuscript witnesses (historical copies) of the Hebrew Bible: the Septuagint, the Masoretic Text, and the Samaritan Pentateuch. Existing complete copies of the Septuagint, a translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, date from the 3rd to the 5th centuries CE, with fragments dating back to the 2nd century BCE.

There is no scholarly consensus as to when the Jewish Hebrew Bible canon was settled in its present form. Some scholars argue that it was fixed by the Hasmonean dynasty (140–40 BCE), while others argue it was not fixed until the second century CE or even later. The Masoretic Text, in Hebrew and Aramaic, is considered the authoritative text by Rabbinic Judaism, but there is also the Septuagint, a Koine Greek translation from the third and second centuries BCE, which largely overlaps with the Hebrew Bible.

Christianity began as an outgrowth of Judaism, using the Septuagint as the basis of the Old Testament. The early Church continued the Jewish tradition of writing and incorporating what it saw as inspired, authoritative religious books, and soon the gospels, Pauline epistles and other texts coalesced into the "New Testament". In its first three centuries AD, the concept of a closed canon emerged in response to heretical writings in the second century. A first list of canonical books appears in Athanasius' Easter letter from 367 AD. The list of books included in the Catholic Bible was established as the biblical canon by the Council of Rome in 382, followed by that of Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397. Christian biblical canons include the Catholic Church canon, the canon of most Protestant denominations, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church canon, among others.

Divine inspiration

The Second Epistle to Timothy says that "all scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness". (2 Timothy 3:16) Various related but distinguishable views on divine inspiration include:

- the view of the Bible as the inspired word of God: the belief that God, through the Holy Spirit, intervened and influenced the words, message, and collation of the Bible

- the view that the Bible is also infallible, and incapable of error in matters of faith and practice, but not necessarily in historic or scientific matters

- the view that the Bible represents the inerrant word of God, without error in any aspect, spoken by God and written down in its perfect form by humans

Within these broad beliefs many schools of hermeneutics operate. "Bible scholars claim that discussions about the Bible must be put into its context within church history and then into the context of contemporary culture." Fundamentalist Christians are associated with the doctrine of biblical literalism, where the Bible is not only inerrant, but the meaning of the text is clear to the average reader.

Jewish antiquity attests to belief in sacred texts, and a similar belief emerges in the earliest of Christian writings. Various texts of the Bible mention divine agency in relation to its writings. In their book A General Introduction to the Bible, Norman Geisler and William Nix write: "The process of inspiration is a mystery of the providence of God, but the result of this process is a verbal, plenary, inerrant, and authoritative record." Most evangelical biblical scholars associate inspiration with only the original text; for example some American Protestants adhere to the 1978 Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy which asserted that inspiration applied only to the autographic text of scripture. Among adherents of biblical literalism, a minority, such as followers of the King-James-Only Movement, extend the claim of inerrancy only to a particular version.

Translations

Nearly all modern English translations of the Old Testament are based on a single manuscript, the Leningrad Codex also called the St. Petersburg Codex, copied in 1008 or 1009. It is a complete example of the Masoretic Text, and its published edition is used by the majority of scholars. The Aleppo Codex is the basis of the Hebrew University Bible Project in Jerusalem. Copied about 925 CE, part of it was lost, so it must rely on additional manuscripts, and as a result, the Aleppo Codex contains the most comprehensive collection of variant readings.

The earliest Latin translation was the Old Latin text, or Vetus Latina, which, from internal evidence, seems to have been made by several authors over a period of time. It was based on the Septuagint, and thus included books not in the Hebrew Bible.

According to the Latin Decretum Gelasianum (also known as the Gelasian Decree), thought to be of a 6th-century document of uncertain authorship and of pseudepigraphal papal authority (variously ascribed to Pope Gelasius I, Pope Damasus I, or Pope Hormisdas) but reflecting the views of the Roman Church by that period, the Council of Rome in 382 CE under Pope Damasus I (366–383) gives a complete list of the canonical books of both the Old Testament and the New Testament which is identical with the list given at the Council of Trent.

Damasus commissioned Saint Jerome to produce a reliable and consistent text by translating the original Greek and Hebrew texts into Latin. This translation became known as the Latin Vulgate Bible, in the 4th century CE (although Jerome expressed in his prologues to most deuterocanonical books that they were non-canonical). In 1546, at the Council of Trent, Jerome's Vulgate translation was declared by the Roman Catholic Church to be the only authentic and official Bible in the Latin Church.

Since the Protestant Reformation, Bible translations for many languages have been made. The Bible continues to be translated to new languages, largely by Christian organizations such as Wycliffe Bible Translators, New Tribes Mission and Bible societies.

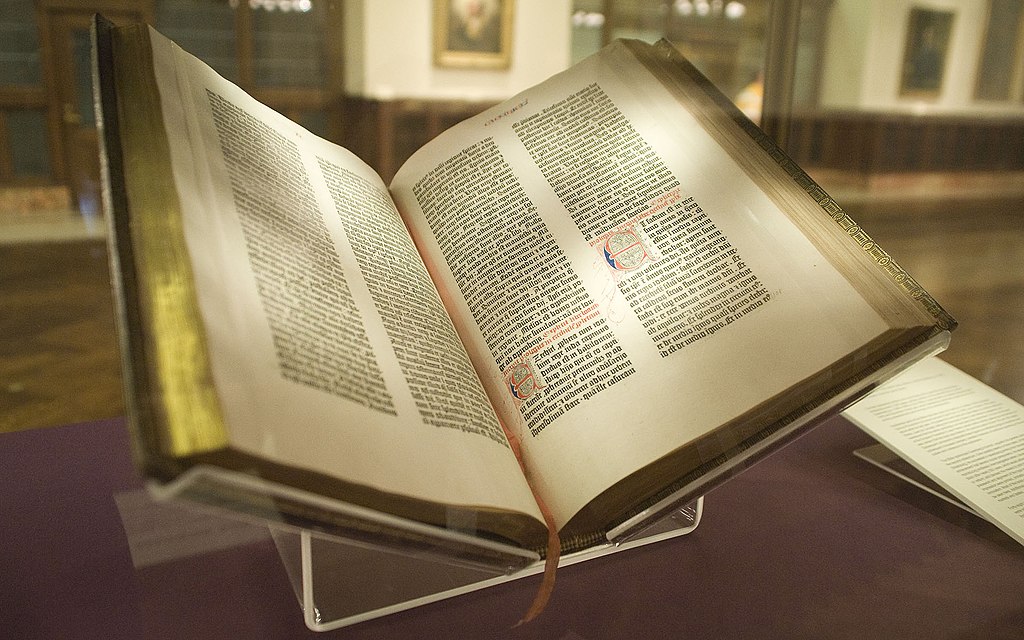

The Gutenberg Bible was the earliest major book printed using mass-produced movable metal type in Europe. It marked the start of the "Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of printed books in the West.

Historical accuracy

The historicity of the biblical account of the history of ancient Israel and Judah of the 10th to 7th centuries BCE is disputed in scholarship. The biblical account of the 8th to 7th centuries BCE is widely, but not universally, accepted as historical, while the earliest period of the United Monarchy (10th century BCE) and the historicity of David has only recently been established due to archaeological evidence such as the Tel Dan Stele. The biblical account of events of the Exodus from Egypt in the Torah, and the migration to the Promised Land and the period of Judges are generally not considered historical, although this too remains open to further evidence.