Emerald Tablet

The Emerald Tablet is a compact and cryptic Hermetic text. It was a highly regarded foundational text for many Islamic and European alchemists. Though attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, the text of the Emerald Tablet first appears in a number of early medieval Arabic sources, the oldest of which dates to the late eighth or early ninth century. It was translated into Latin several times in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Numerous interpretations and commentaries followed.

Medieval and early modern alchemists associated the Emerald Tablet with the creation of the philosopher's stone and the artificial production of gold.

It has also been popular with occultists and esotericists since the 1800s, among whom the expression "as above, so below" (a modern paraphrase of the second verse of the Tablet) has become an often cited motto.

Background

Beginning from the 2nd century BC onwards, Greek texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth, appeared in Greco-Roman Egypt. These texts, known as the Hermetica, are a heterogeneous collection of works that in the modern day are commonly subdivided into two groups:

- technical Hermetica, comprising astrological, medico-botanical, alchemical, and magical writings

- religio-philosophical Hermetica, comprising mystical-philosophical writings.

These Greek pseudepigraphal texts found receptions, translations and imitations in Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and Middle Persian prior to the emergence of Islam and the Arab conquests in the 630s. These developments brought about various Arabic-speaking empires in which a new group of Arabic-speaking intellectuals emerged. These scholars received and translated the before-mentioned wealth of texts and also began producing Hermetica of their own.

"Emerald" aspect

Emerald is the stone traditionally associated with Hermes, while mercury is his metal. Mars is associated with red stones and iron, and Saturn is associated with black stones and lead. In antiquity, Greeks and Egyptians referred to various green-coloured minerals (green jasper and even green granite) as emerald, and in the Middle Ages, this also applied to objects made of coloured glass, such as the "Emerald Tablet" of the Visigothic kings or the Sacro Catino of Genoa (a dish seized by the Crusaders during the sack of Caesarea in 1011, which was believed to have been offered by the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon and used during the Last Supper).

This version of the Emerald Tablet is also found in the Kitab Ustuqus al-Uss al-Thani (Elementary Book of the Foundation) attributed to the 8th-century alchemist Jâbir ibn Hayyân, known in Europe by the latinized name Geber.

Original Arabic versions

The literary theme of the discovery of Hermes' hidden wisdom can be found in other Arabic texts from around the 10th century. A similar account can be found in the Latin text known as Tabula Chemica by Senior Zadith, the latinized name of the alchemist Ibn Umail, in which a stone table rests on the knees of Hermes Trismegistus in the secret chamber of a pyramid. Here, the table is not inscribed with text but with "hieroglyphic" symbols.

Book of the Secret of Creation

The Emerald Tablet has been found in various ancient Arabic works in different versions. The oldest version is found as an appendix in a treatise believed to have been composed in the 9th century, known as the Book of the Secret of Creation. This text presents itself as a translation of Apollonius of Tyana, under his Arabic name Balînûs. Although no Greek manuscript has been found, it is plausible that an original Greek text existed. The attribution to Apollonius, though false (pseudonymous), is common in medieval Arabic texts on magic, astrology, and alchemy.

The introduction to the Book of the Secret of Creation is a narrative that explains, among other things, that all things are composed of four elemental principles: heat, cold, moisture, and dryness (the four qualities of Aristotle), and their combinations account for the elations of sympathy and antipathy between beings.

Balînûs, "master of talismans and wonders," enters a crypt beneath the statue of Hermes Trismegistus and finds the emerald tablet in the hands of a seated old man, along with a book. The core of the work is primarily an alchemical treatise that introduces for the first time the idea that all metals are formed from sulfur and mercury, a fundamental theory of alchemy in the Middle Ages. The text of the Emerald Tablet appears last, as an appendix. It has long been debated whether it is an extraneous piece, solely cosmogonic in nature, or if it is an integral part of the rest of the work, in which case it has an alchemical significance from the outset. Recently, it has been suggested that it is actually a text of talismanic magic and that the confusion arises from a mistranslation from Arabic to Latin.

Secret of Secrets

Another version is found in an eclectic Arabic book from the 10th century, the Secretum Secretorum (Secret of Secrets), which presents itself as a pseudo-letter from Aristotle to Alexander the Great during the conquest of Persia. It discusses politics, morality, physiognomy, astrology, alchemy, medicine, and more. The text is also attributed to Hermes but lacks the narrative of the tablet's discovery.

Latin translations

The Book of the Secret of Creation was translated into Latin (Liber de secretis naturae) in c. 1145–1151 by Hugo of Santalla. This text does not appear to have been widely circulated.

The Secret of Secrets was translated into Latin in an abridged 188 lines long medical excerpt by John of Seville around 1140. The first full Latin translation of the text was prepared by Philip of Tripoli around a century later. This work has been called "the most popular book of the Latin Middle Ages."

A third Latin version can be found in an alchemical treatise dating probably from the 12th century (although no manuscripts are known before the 13th or 14th century), the Liber Hermetis de alchimia (Book of Alchemy of Hermes). This version, known as the "vulgate," is the most widespread. The translator of this version did not understand the Arabic word tilasm, which means talisman, and therefore merely transcribed it into Latin as telesmus or telesmum. This accidental neologism was variously interpreted by commentators, thereby becoming one of the most distinctive, yet vague, terms of alchemy.

Latin Commentaries

In his 1143 treatise, De essentiis, Herman of Carinthia is one of a few European 12th century scholars to cite the Emerald Tablet. In this text he also recalls the story of the tablet's discovery under a statue of Hermes in a cave from the Book of the Secret of Creation. Carinthia was a friend of Robert of Chester, who in 1144 translated the Liber de compositione alchimiae, which is generally considered to be the first Latin translation of an Arabic treatise on alchemy.

Around 1275–1280, Roger Bacon translated and commented on the Secret of Secrets, and through a completely alchemical interpretation of the Emerald Tablet, made it an allegorical summary of the Great Work.

Renaissance writings

During the Renaissance, the idea that Hermes Trismegistus was the founder of alchemy gained prominence, and at the same time, the legend of the discovery evolved and intertwined with biblical accounts. This is particularly the case in the late 15th century in the Livre de la philosophie naturelle des métaux by the pseudo-Bernard of Treviso, who wrote: "The first inventor of this Art was Hermes Trismegistus, for he knew all three natural philosophies, namely Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal." This text influenced a discovery legend claiming the tablet to have been discovered after the Biblical Flood in Hebron valley which is connected with the image of the "Emblem of the Smaragdine Tablet" in the 1599 text Aureum Vellus.

The first printed edition appears in 1541 in the De alchemia published by Johann Petreius and edited by "Chrysogonus Polydorus" (likely a pseudonym for the Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander). This version is known as the "vulgate" version and includes the commentary by Hortulanus.

By the early sixteenth century, the writings of Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516) marked a shift away from a laboratory interpretation of the Emerald Tablet, to a metaphysical approach. Trithemius equated Hermes' one thing with the monad of pythagorean philosophy and the anima mundi. This interpretation of the Hermetic text was adopted by alchemists such as John Dee and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa.

Enlightenment thought

From the beginning of the 17th century onward, a number of authors challenge the attribution of the Emerald Tablet to Hermes Trismegistus and, through it, attack antiquity and the validity of alchemy. First among them is a "repentant" alchemist, the Lorraine physician Nicolas Guibert, in 1603. But it is the Jesuit scholar and linguist Athanasius Kircher who launches the strongest attack in his monumental work Oedipus Aegyptiacus (Rome, 1652–1653). He notes that no texts speak of the Emerald Tablet before the Middle Ages and that its discovery by Alexander the Great is not mentioned in any ancient testimonies. By comparing the vocabulary used with that of the Corpus Hermeticum (which had been proven by Isaac Casaubon in 1614 to date only from the 2nd or 3rd century AD), he affirms that the Emerald Tablet is a forgery by a medieval alchemist. As for the alchemical teaching of the Emerald Tablet, it is not limited to the philosopher's stone and the transmutation of metals but concerns "the deepest substance of each thing," the alchemists' quintessence.

Wilhelm Christoph Kriegsmann argued in 1684 that Hermes Trismegistus is not the Egyptian Thoth, but the Taaut of the Phoenicians, who is also the founder of the Germanic people under the name of the god Tuisto, mentioned by Tacitus.

Danish alchemist Ole Borch attempted to separate the hermetic texts between the late writings and those truly attributable to the ancient Egyptian Hermes, among which he inclines to classify the Emerald Tablet.

1800s to Modern era

Alchemy and its foundational text continued to interest occultists in the early modern era. This is the case with magician Éliphas Lévi, who wrote: "Nothing surpasses and nothing equals as a summary of all the doctrines of the old world the few sentences engraved on a precious stone by Hermes and known as the 'emerald tablet'... it is all of magic on a single page."

It also applies to the "curious figure" of the German Gottlieb Latz, who self-published a monumental work Die Alchemie in 1869, as well as the theosophist Helena Blavatsky.

At the beginning of the 20th century, alchemical thought resonated with the surrealists, and André Breton incorporated the main axiom of the Emerald Tablet into the Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1930):

"Everything leads us to believe that there exists a certain point of the spirit from which life and death, the real and the imaginary, the past and the future, the communicable and the incommunicable, the high and the low, cease to be perceived as contradictory. However, in vain would one seek any motive other than the hope for the determination of this point in surrealist activity."

Isaac Newton's translation

Despite some small differences, the 16th-century Nuremberg edition of the Latin text remains largely similar to the vulgate (see above). A translation by Isaac Newton is found among his alchemical papers that are currently housed in King's College Library, Cambridge University:

Tis true without lying, certain and most true.

That which is below is like that which is above and that which is above is like that which is below

to do the miracle of one only thing

And as all things have been and arose from one by the mediation of one: so all things have their birth from this one thing by adaptation.

The Sun is its father, the moon its mother,

the wind hath carried it in its belly, the earth is its nurse.

The father of all perfection in the whole world is here.

Its force or power is entire if it be converted into earth.

Separate thou the earth from the fire,

the subtle from the gross

sweetly with great industry.

It ascends from the earth to the heaven and again it descends to the earth

and receives the force of things superior and inferior.

By this means you shall have the glory of the whole world and thereby all obscurity shall fly from you.

Its force is above all force,

for it vanquishes every subtle thing and penetrates every solid thing.

So was the world created.

From this are and do come admirable adaptations where of the means is here in this.

Hence I am called Hermes Trismegist, having the three parts of the philosophy of the whole world.

That which I have said of the operation of the Sun is accomplished and ended.

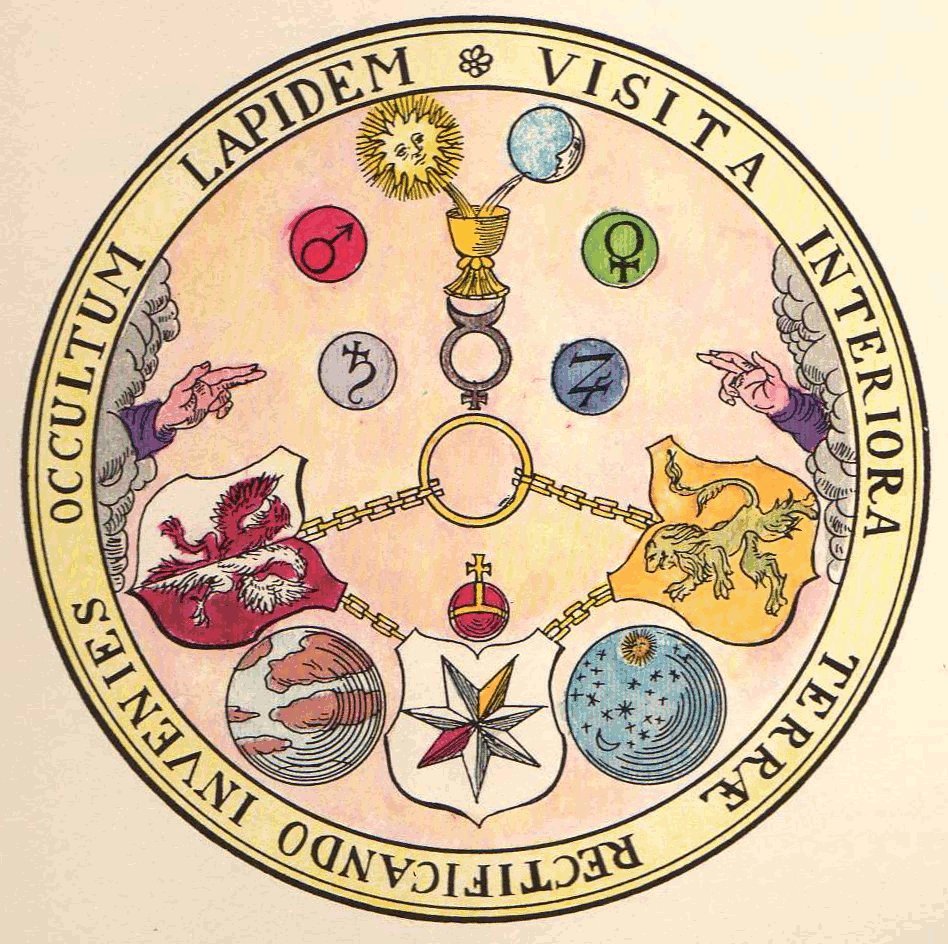

Tabula Smaragdina Hermetis emblem

From the late 16th century onwards, the Emerald Tablet is often accompanied by a symbolic figure called the Tabula Smaragdina Hermetis.

This figure is surrounded by an acrostic in Latin: Visita interiora terrae rectificando invenies occultum lapidem, lit. "visit the interior of the earth and by rectifying you will find the hidden stone" whose seven initials form the word Old French: vitriol, lit. 'sulphuric acid'.

At the top, the sun and moon pour into a cup above the symbol of mercury. Around the mercurial cup are the four other planets, representing the classic association between the seven planets and the seven metals:

The oldest known reproduction is a copy dated 1588-89 of a manuscript that was circulating anonymously at the time and was likely written in the second half of the 16th century by a German Paracelsian. The image was accompanied by a didactic alchemical poem in German titled Du secret des sages, probably by the same author. The poem explains the symbolism in relation to the Great Work and the classical goals of alchemy: wealth, health, and long life.

In popular culture

In 1974, Brazilian singer Jorge Ben Jor recorded a studio album under the name A Tábua de Esmeralda ("The Emerald Tablet"), quoting from the Tablet's text and from alchemy in general in several songs. The album has been defined as an exercise in "musical alchemy" and celebrated as Ben Jor's greatest musical achievement, blending together samba, jazz, and rock rhythms.

The 2014 occult horror film, As Above, So Below, refers to the popular paraphrase of the second verse of the Emerald Tablet. It is presented as found footage of a documentary crew's experience exploring the Catacombs of Paris in search of the philosopher's stone.