Umbanda

Umbanda is a religion that emerged in Brazil during the 1920s. Deriving largely from Spiritism, it also combines elements from Afro-Brazilian traditions like Candomblé as well as Roman Catholicism.

There is no central authority in control of Umbanda, which is organized around autonomous places of worship termed centros or terreiros, the followers of which are called Umbandistas.

Beliefs

Umbandist theology is largely Spiritist in basis, adopting the Spiritist emphasis on reincarnation and spiritual evolution as well as the hierarchical ranking of spirits according to their "degree of evolution." Umbanda teaches that everyone has a spirit that survives bodily death and goes on successive reincarnations, seeking ever higher levels of spiritual evolution.

Conception of God

Umbanda is monotheistic. It believes in a single God who is the creator and controller of the universe, an entity that presides over the astral world but who is distant from humanity. He is sometimes called Olorun, a name of Yoruba origin. Beneath God is a pantheon of spirits that reflect origins from numerous traditions including the Abrahamic religions. These spirits are assembled into a complex, impersonal bureaucracy, in order to intervene in humanity's daily lives in a fashion similar to saints or angels.

Cosmology

Many Umbandistas believe in a three-part cosmos, divided between the astral spaces, the earth, and the underworld. The more highly evolved spirits dwell in the astral realm, spirits incarnated in physical form reside temporarily on earth, while malevolent and ignorant spirits inhabit the underworld. The barrier between these worlds is not impenetrable; spirits from both the astral and underworld realms can visit the earth. Umbandistas often refer to the plano astral (astral plane) as the além (beyond). Sometimes, the realm of the evolved spirits is also called Aruanda.

Seven Lines

The astral world is deemed to be divided into a hierarchy of seven vertical levels, the Sête Linhas de Umbanda (Seven Lines of Umbanda), although the specific identity of each line varies among Umbandistas. This seven-fold division may derive from Theosophy. Each of the Seven Lines is governed by an orixá, a highly evolved spirit who will also have an identity as a Roman Catholic saint.

The underworld is also divided into Seven Lines, each of which is led by an exú spirit. Each Line is also internally divided into seven sub-lines; each of these is then divided into seven legions; these divide into seven sub-legions; these into seven falanges (phalanxes); and these into seven sub-falanges. Umbandistas often liken this cosmological structure to the organization of an army, and it may reflect the prominent role that various military figures have played in Umbanda's history. The spirits inhabiting these groups are usually arranged on the basis of regional or racial origin.

Orixás

Orixás are God's intermediaries, and represent elemental forces of nature as well as humanity's primary economic activities. White Umbandist groups often perceive the orixás primarily as frequencies of spiritual energy, vibrations, or forces. They are regarded as beings so highly evolved that they have never incarnated in physical form. Like God, they are distant from humanity, permanently residing on the astral plane.

Each of the orixás is deemed to have their own desires and emotions. The orixás are also associated with particular colors; Oxúm with blue, for instance, and Oxóssi with green. Each is also linked to particular days of the week; Iansã with Wednesday, and Nanã with Tuesday, for example. They are also associated with a particular celestial body, such as Xangô with the planet Jupiter and Iemanjá with the moon.

Each orixá is typically associated with a Roman Catholic saint. It is in this form that they are often represented on Umbandist altars.

Caboclos and pretos velhos

Many Umbandistas rarely expect orixás to manifest during rituals, for the orixás are preoccupied with important spiritual matters. They are also thought too powerful for many humans to handle, meaning that their manifestation could be dangerous for the ritual's participants. Instead, the orixás send their emissaries, the caboclos and pretos velhos, to appear in their place.

Caboclos are usually the spirits of indigenous Brazilians, especially those from the Amazon Rainforest. They are hunters and warriors who are highly intelligent and brave, but also vain and arrogant. Their power comes from the forces of nature, including the sun and moon, waterfalls, and the forest.

Pretos velhos ("old blacks") are usually, although not always, regarded as the spirits of deceased African slaves. Despite the suffering they endured in life, they preach forgiveness and love. They are healers and counsellors, spirits to whom Umbandistas can bring their problems. When a medium deems themselves possessed by one of the pretos velhos, they will often smoke a pipe.

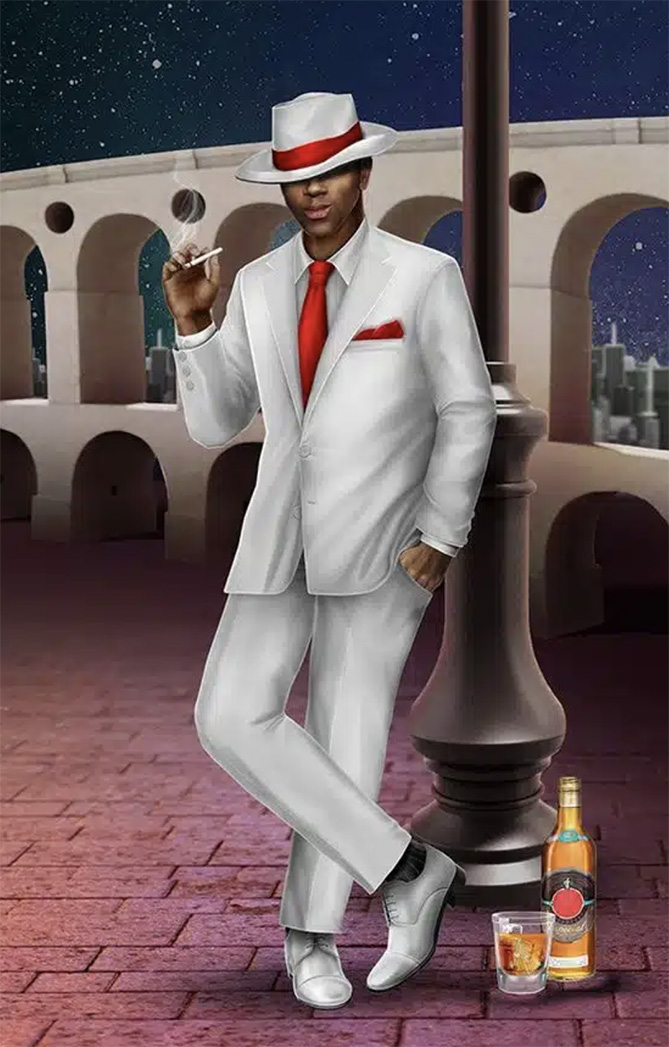

Exús and pombagiras

The exús are spirits yet to complete the process of karmic evolution. They are unevolved spirits of darkness which, by working for good, can gradually become spirits of light. Interpretations of these exús nevertheless differ among Umbandistas, with more African-oriented practitioners often taking a more positive attitude towards them. Exús are associated with Friday, and with the colors red and black. They are also linked to the obtaining of power, money, and sex. One of the most recognizable spirits considered an exú is Zé Pilintra, although he is also viewed as a pretos velhos.

The female counterparts of the exús, pombagiras are regarded as being the spirits of immoral women, such as prostitutes. They are linked to marginal and dangerous places, and associated with sexuality, blood, death, and cemeteries.

Other spirits

Below the caboclos and pretos velhos in the Seven Lines of the astral realm are a large number of unidentified guias (spirit guides) and espíritos pretetores (spirit protectors). Other types of spirit found in Umbanda include:

- the boiadeiros (cowboys)

- crianças (children)

- marinheiros (sailors)

- malandros (rogues)

- ciganos (gypsies)

- sereias (mermaids)

Mediumship

Central to Umbanda are the spirit mediums, individuals responsible for channeling the good spirits. Umbandistas believe that the skill of mediumship is innate to certain individuals. Around two-thirds of Umbandist mediums are female and a third are male. Most Umbandist mediums take on this role as a result of an initial personal crisis, often physical illness or emotional distress, that they come to believe is being caused by spirits as a means of alerting them.

Reciprocity is expected when engaging with the spirits, with those seeking their services often providing them with gifts. A person's misfortunes may be interpreted as a reminder that obligations to the spirits have not been met. Many Umbandistas believe that a good medium should maintain a healthy and pure body, for this reason avoiding smoking, over-eating, or drinking alcohol, especially on the night of an Umbandista session.

Morality

Umbandist morality places key emphasis on caridade (charity). Its belief system inherited the Roman Catholic view that the world was a battleground between good and evil. The term Quimbanda is often used to describe all things associated with evil, immorality, and pollution. In Brazil, there are individuals who call themselves Quimbandeiros and openly practice Quimbanda.

The orixá Oxumaré, as an entity that spends six months being male and six months being female, is sometimes cited as a patron of gay and bisexual people.

Practices

Umbandist practices often revolve around clients who approach practitioners seeking assistance, for instance in diagnosing a problem, healing, or receiving a blessing. In Umbanda, spiritual knowledge and ethical behaviour are generally seen as being more important than ritual action.

Worship

Umbandist places of worship are termed centros, or alternatively tendas (tents). Those adopting a more African-orientation are sometimes called terreiros, but this term comes from Candomblé, and so is avoided by some practitioners of White Umbanda.

Each centro will typically have its own Padroeiro, or patron spirit. They are often totally autonomous, although some are members of larger Umbandist federations. A centro may occupy a purpose-built structure although may be based out of someone's home.

Possession

The gira is a dance to celebrate the orixás; the members of the ritual corps will often dance in a procession. During the gira, some participants will become possessed, ceasing to dance and instead swaying and jerking rapidly.

The possessed medium's facial expressions and demeanour may change to reflect the entity within them, while attendants may dress them in a manner suited to this spirit, for instance with the giving of feathered headdresses to those possessed by caboclos.

Once all of the spirits are believed to have arrived, the singing and dancing will stop and the consultations will begin.

If exús possess a medium during the session, they will generally be exorcised.

History

Umbanda is generally regarded as having emerged in the area around Rio de Janeiro during the 1920s. There is a lack of clear evidence regarding Umbanda's foundations and it is possible that it emerged from multiple origins around the same time, with various early 20th-century groups having combined Spiritist and Afro-Brazilian religious practices.

Zélio Fernandino de Moraes

A key figure was Zélio Fernandino de Moraes, founder of the first Umbandist group, the Centro Espírita Nossa Senhora da Piedade (Spiritism Center of Our Lady of Mercy). This initially operated in Niterói from the mid-1920s before moving to the center of Rio de Janeiro in 1938.

In 1908, when he was 17 years old, Moraes had been cured of an illness by a highly evolved spirit. His parents then took him to a Spiritist ritual, where the spirit Caboclo Seven Crossroads incorporated into him. This spirit defended the appearance of African and indigenous spirits that then incorporated in other mediums, despite the Spiritist prejudice towards them.

Competition

In response to the growth of Umbanda, Spiritism, and Pentecostalism, Brazil's dominant Roman Catholic Church mounted a campaign against these minority religions, one later formally terminated due to the changes of the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s.

During the 1970s, Candomblé spread from Bahia into São Paulo, where it grew rapidly, largely at the expense of Umbanda. Some Umbanda temples transformed into Candomblé temples. Conversely, Umbanda saw growth in northern Brazil during this period. The 1970s also saw the rise in attempts to "re-Africanize" Umbanda by emphasising African elements, reflecting a broader revival of interest in African cultural heritage among Afro-Brazilians.

Some Umbandistas move on to join Candomblé, believing that the latter deals with more powerful supernatural forces and thus resolves problems more readily.

Umbanda has also influenced some practitioners of Santo Daime, and a tradition called Umbandaime has emerged as a hybridized religion combining elements of both.

Demographics

In the 2000 Brazilian census, only 397,000 people identified as Umbandistas, with likely more than a million additional people infrequently attending services during times of personal crisis. Although originally concentrated in Brazil's large southern cities, the religion has spread throughout the country.

White Umbandist centros typically have a diverse socio-economic membership, while Africanized Umbandist terreiros have particular appeal for "people in the entertainment world and the arts," gay people, and those in "the upper sectors" of society who were interested in alternative lifestyles.