Black Mass

A Black Mass is a ceremony typically celebrated by various Satanic groups. It has allegedly existed for centuries in different forms and is directly based on, and is intentionally a sacrilegious and blasphemous mockery of, a Catholic Mass.

In the 19th century the Black Mass became popularized in French literature. Modern revivals began with H. T. F. Rhodes' book The Satanic Mass published in London in 1954, and there is now a range of modern versions of the Black Mass performed by various religious groups.

Early development

The Catholic Church regards the Mass as its most important ritual, going back to apostolic times. However, as early Christianity became more established and its influence began to spread, the early Church Fathers encountered heretical sects practicing their own versions of the Mass. Some of these rituals were of a sexual nature.

The fourth-century AD heresiologist Epiphanius of Salamis, for instance, claims that a libertine Gnostic sect known as the Borborites engaged in a version of the Eucharist in which they would smear their hands with menstrual blood and semen and consume them as the blood and body of Jesus Christ. He also said whenever one of the women in their church was experiencing her period, they would take her menstrual blood and everyone in the church would eat it as part of a sacred ritual.

Private Masses

Within the Catholic Church, the rite of the Mass was not completely fixed, priests would hire their services out to perform Masses for the needs of their clients. The most common were blessing crops or cattle, achieving success in some enterprise, obtaining love, or cursing enemies (one way this latter was done was by inserting the enemy's name in a Mass for the dead, accompanied by burying an image of the enemy). Although these practices were condemned by Church authorities as superstitious and sacrilegious abuses, they still occurred secretively. In the 12th and 13th centuries there was a great surplus of clerics and monks who might be inclined to perform these Masses.

Medieval parody Masses

The ritual of the Mass was sometimes reworked to create light-hearted parodies of it for certain festivities. Some of these became quasi-tolerated practices at times—though never accepted by official Church authorities—such as a festive parody of the Mass called "The Feast of Asses," in which Balaam's ass (from the Old Testament) would begin talking and saying parts of the Mass. A similar parody was the Feast of Fools.

There began to appear more cynical and heretical parodies of the Mass, also written in ecclesiastical Latin, known as "drinkers' Masses" and "gamblers' Masses," which lamented the situation of drunk, gambling monks, and instead of calling to God, called to Bacchus and Decius. Some of the earliest of these Latin parody works are found in the medieval Latin collection of poetry, Carmina Burana, written around 1230. At the time these wandering clerics were spreading their Latin writings and parodies of the Mass, the Cathars, who also spread their teachings through wandering clerics, were also active.

Connection with witchcraft

A further source of late Medieval and Early Modern involvement with parodies and alterations of the Mass, were the writings of the European witch-hunt, which saw witches as being agents of the Devil, who were described as inverting the Christian Mass and employing the stolen Host for diabolical ends. Witch-hunter's manuals such as the Malleus Maleficarum (1487) and the Compendium Maleficarum (1608) allude to these practices, although they bore little basis in reality. The first complete depiction of a blasphemy of the Mass in connection with the witches' sabbath, was given in Florimond de Raemond's 1597 French work, The Antichrist (written as a Catholic response to the Protestant claim that the Pope was the Antichrist).

The most sophisticated and detailed descriptions of the Black Mass to have been produced in early modern Europe are found in the Basque witch-hunts of 1609–1614. It has recently been argued by academics including Emma Wilby that the emphasis on the Black Mass in these trials evolved out of a particularly creative interaction between interrogators keen to find evidence of the rite and a Basque peasants who were deeply committed to a wide range of unorthodox religious practices such as "cursing" Masses, liturgical misrule and the widespread misuse of Catholic ritual elements in forbidden magical conjurations.

French practitioners of Black Mass

Catherine de' Medici, the 16th century Queen of France, was said by Jean Bodin to have performed a Black Mass, based on a story in his 1580 book on witchcraft De la démonomanie des sorciers. She was widely distrusted by the French people due in part to her Italian heritage and her hiring of Nostradamus as her personal astrologer. In spite of Bodin's lurid details, there is little outside evidence to back up his story.

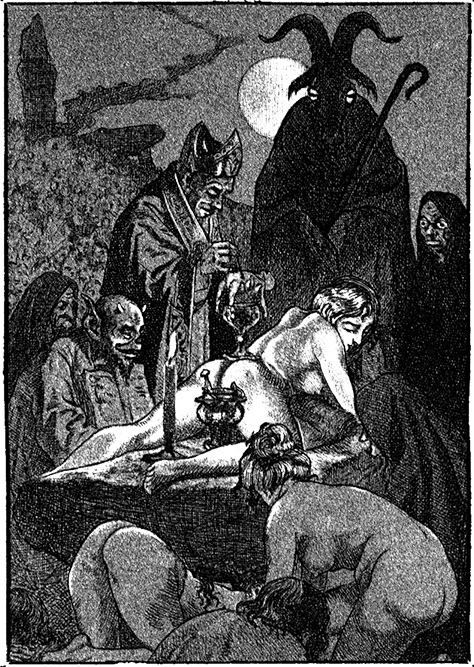

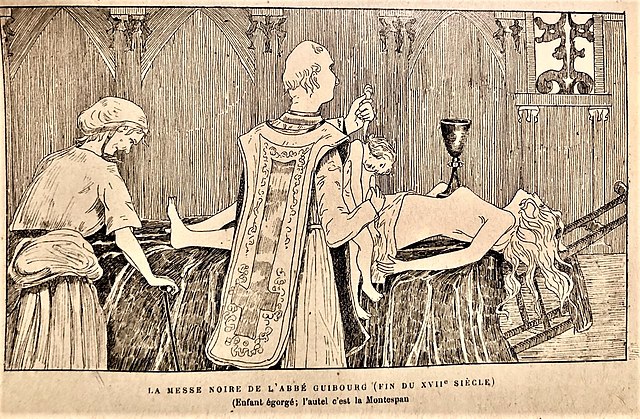

In the 17th century, Catherine Monvoisin and the priest Étienne Guibourg performed Black Masses for Madame de Montespan, the mistress of King Louis XIV of France. Since a criminal investigation—L'affaire des poisons ("Affair of the Poisons")—was launched and testimony from those involved revealed the details of this Masses.

At this time, the Black Mass was a typical Roman Catholic Mass, but modified according to certain formulas (some reminiscent of the Sworn Book of Honorius, or its French version, The Grimoire of Pope Honorius). The priest utilized a woman as the central altar of worship, lying naked upon the altar with the chalice on her stomach, and holding a candle in each of her outstretched arms. The Host was consecrated in her vagina, and then used in love potions designed to gain the love of the King. To seal the power of the Mass, the priest had sex with the woman serving as the altar at the end of the ritual.

Modern Black Masses

In spite of the huge amount of French literature discussing the Black Mass (Messe Noire) at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century, no set of written instructions for performing one, from any purported group of Satanists, turned up in writing until the 1960s. As can be seen from these first Black Masses and Satanic Masses appearing in the U.S., the creators drew heavily from occult novelists such as Dennis Wheatley and Joris-Karl Huysmans, and from non-fiction occult writers popular in the 1960s, such as Grillot de Givry, author of the popular illustrated book Witchcraft, Magic and Alchemy, and H. T. F. Rhodes.

Herbert Sloane, the founder of an early Satanist group, the Ophite Cultus Satanas, speaks of Satanists performing the ritual of the "Satanic Mass" in a letter he wrote in 1968 (see the article on his group), and in 1968 and 1969 also appeared the first two recordings of Satanic rituals, both entitled the "Satanic Mass." Soon after the band Coven released a Satanic Mass recording, the Church of Satan began creating their own Black Masses, two of which are available to the public.

A writer using the pseudonym "Aubrey Melech" published, in 1986, a Black Mass entirely in Latin, entitled "Missa Niger." (This Black Mass is available on the Internet). Aubrey Melech's Black Mass contains almost exactly the same original Latin phrases as the Black Mass published by Anton LaVey in The Satanic Rituals. LaVey and Melech did not give their sources for the Latin material in their Black Mass, merely implying that they received it from someone else.

In his 2023 book SEXCRAFT, occultist Travis McHenry gave three different types of Black Mass rituals with varying degrees of intensity.

Language of the black mass

The Latin of Melech and LaVey is based on the Roman Catholic Latin Missal, reworded so as to give it a Satanic meaning. Both Black Masses end with the Latin expression "Ave, Satanas!" (meaning either "Welcome, Satan!", or "Hail Satan!").

In La Voisin's version of the Black Mass, the priest performed a ritual invocation to the demonic spirits they were attempting to ask for help.

"Astaroth, Asmodeus, princes of friendship, I conjure you to accept the sacrifice I offer you of this child for the things I ask of you, which are that the friendship of the King and le Dauphin may continue towards me, and that I may be honored by the princes and princess of the court, and that nothing I ask of the King may be denied me, either for my relatives or servants."

Scholarly evaluations

The French historian Jules Michelet was one of the first to analyze and attempt to understand the Black Mass, and wrote two chapters about it in his classic book, Satanism and Witchcraft (1862).

J. G. Frazer included a description of the Mass of Saint-Sécaire, an unusual French legend with similarities to the Black Mass, in The Golden Bough (1890). Frazer was recounting material already found in an 1883 French book entitled Quatorze superstitions populaires de la Gascogne (Fourteen Popular Superstitions of Gascony), by Jean-François Bladé. This Mass was said to be employed as a method of assassination by supernatural means, allowing the supplicant to avenge himself if he was wronged by someone.

Montague Summers discussed many classic portrayals of the Black Mass in a number of his works (especially in The History of Witchcraft and Demonology (1926) with extensive quotations from the original French and Latin sources).

H. T. F. Rhodes' book, The Satanic Mass, published in London in 1954, was a major inspiration for modern versions of the Black Mass, when they finally appeared. Rhodes claimed that, at the time of his writing, there did not exist a single first hand source which actually described the rites and ceremonies of a Black Mass.