Sabbat

The Sabbat, Sabbath, or Shabbat (from Hebrew שַׁבָּת Šabbāṯ) is, depending on the context and the religious tradition, a day set aside for rest, worship, or celebration.

Abrahamic religions treat the sabbath as a day of rest, commanded by Yahweh to be kept as a holy day of rest. The practice of observing the Sabbath (Shabbat) originates in the biblical commandment "Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy" (Exodus 20:8–11). The sabbath is observed in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Observances similar to, or descended from, the sabbath also exist in other religions. The term may be generally used to describe similar observances in other religions.

Biblical sabbath

Sabbath (as the verb שָׁבַת֙ shabbat) is first mentioned in the Genesis creation narrative, where the seventh day is set aside as a day of rest and made holy by God (Genesis 2:2–3). Observation and remembrance of Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments. Most Jews who observe the Sabbath regard it as having been instituted as a perpetual covenant for the Israelites. However, most Sabbath-keeping Christians regard the Sabbath as having been instituted by God at the end of Creation week and that the entire world was then, and continues to be, obliged to observe the seventh day as Sabbath.

Originally, Sabbath-breakers were officially to be cut off from the assembly or potentially killed. Observance in the Hebrew Bible was universally from sixth-day sundown to seventh-day sundown (Nehemiah 13:19, cf. Leviticus 23:32), on a seven-day week. Consultations with prophets (II Kings iv. 23) were sought on the Sabbath. Sabbath corporate worship was not prescribed for the community at large, and the Sabbath activities at the shrines were originally a convocation of priests for the purpose of offering divine sacrifices, with family worship and rest being centered in homes.

New moon

The new moon, occurring every 29 or 30 days, is an important, separately sanctioned occasion in Judaism and some other faiths. Some messianic and Pentecostal churches hold the day of the new moon as Sabbath or rest day, from evening to evening. New-moon services can last all day.

Some modern sects of Abrahamic religions who are Sabbath-keepers have suggested a Sabbath based on the New Moon citing Psalm 104:19 and Genesis 1:14 as a key prooftexts. Observers recognize the 1st, 8th, 15th, 22nd, and 29th days of the month of the Hebrew Calendar as Sabbath days which should be observed. They reject the 7 day week as non-biblical. The recently discovered Dead Sea Scrolls show the Essene Jewish calendar revealing the first sabbath of the month of Nisan being on the 4th day 3 days after the new moon and kept every 7 days for the rest of the year.

Counting from the new moon, the Babylonians celebrated the 7th, 14th, 21st, and 28th as "holy-days." On these days, officials were prohibited from various activities and common men were forbidden to "make a wish." On each of them, offerings were made to a different god and goddess. Tablets from the 6th-century BCE reigns of Cyrus the Great and Cambyses indicate these dates were sometimes approximate. The lunation of 29 or 30 days basically contained three seven-day weeks, and a final week of nine or ten days inclusive, breaking the continuous seven-day cycle.

According to the Zohar, the demonic entities associated with the qlippoth have free reign on the nights of the New Moons, the exception being when these coincide with a Sabbath day (a relatively rare event). On these days, their power disappears completely.

Pagan traditions

The ancient pagan peoples of Europe differed in the festivals they celebrated. In the British Isles, the Anglo-Saxons primarily celebrated the four solstices and equinoxes, while Insular Celtic peoples primarily celebrated the four midpoints between these.

The four Celtic festivals known to the Gaels were:

Wiccan sabbat

Two neopagan groups in Britain adopted an eight-fold festival calendar in the 1950s: the Bricket Wood coven, a Wiccan group led by Gerald Gardner, and the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, a neo-Druidic group led by Ross Nichols. Popular legend holds that Gardner and Nichols developed the calendar during a naturist retreat, where Gardner advocated celebrating the solstices and equinoxes while Nichols preferred celebrating the four Celtic festivals; ultimately they melded the two sets of festivals into one cycle.

The phrase "Wheel of the Year" was in use by the mid-1960s to describe this yearly cycle of eight sabbats spaced at approximately even intervals throughout the year. Samhain, which coincides with Halloween, is considered the first sabbat of the year.

The precise dates on which festivals are celebrated often vary to some degree, as would the related agricultural milestones of the local region. Celebrations may occur on the astrologically precise quarter and cross-quarter days, the nearest full moon, the nearest new moon, or the nearest weekend for contemporary convenience. The festivals were originally celebrated by peoples in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. Consequently, the traditional timing for seasonal celebrations do not align with the seasons in the Southern Hemisphere or near the equator. Pagans in the Southern Hemisphere often advance these dates by six months to coincide with their own seasons.

An esbat is a ritual observance of the full moon in Wicca and neopaganism. Some groups extend the esbat to include the dark moon and the first and last quarters. "Esbat" and "sabbat" are distinct and are probably not cognate terms, although an esbat is also called "moon sabbat."

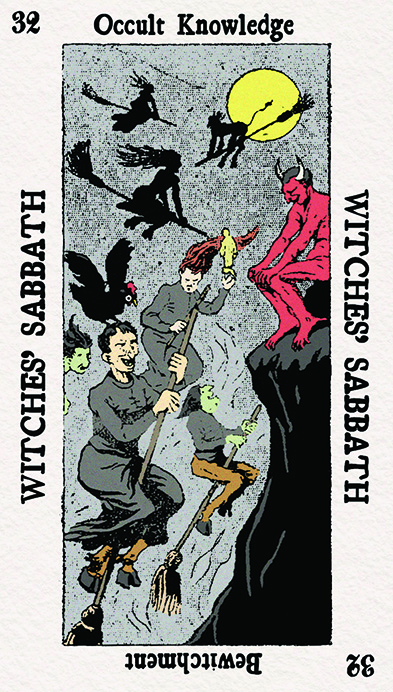

Witchcraft

A Witches' Sabbath is a gathering of witches to practice witchcraft and other rituals. European records from the Middle Ages to the 17th century or later place Witches' Sabbaths on similar dates to sabbats in modern Wicca, but with some disagreement; medieval reports of sabbat activity are generally not firsthand and may be imaginative, but many persons were accused of, or tried for, taking part in sabbats.

The book Compendium Maleficarum (1608) by Francesco Maria Guazzo illustrates a typical view of gathering of witches as "the attendants riding flying goats, trampling the cross, and being re-baptised in the name of the Devil while giving their clothes to him, kissing his behind, and dancing back to back forming a round."

Many of the diabolical elements of the Witches' Sabbath stereotype, such as the eating of babies, poisoning of wells, desecration of hosts or kissing of the devil's anus, were also made about heretical Christian sects, lepers, Muslims, and Jews.

Authenticity of Witches' Sabbaths

The descriptions of Sabbats were made or published by priests, jurists and judges who never took part in these gatherings, or were transcribed during the process of the witchcraft trials. That these testimonies reflect actual events is for most of the accounts considered doubtful. Some of the existing accounts of the Sabbat were given when the person recounting them was being tortured, and so motivated to agree with suggestions put to them.

In his study "The Pursuit of Witches and the Sexual Discourse of the Sabbat," historian Scott E. Hendrix presents a two-fold explanation for why these stories were so commonly told in spite of the fact that sabbats likely never actually occurred. First, belief in the real power of witchcraft grew during the late medieval and early-modern Europe as a doctrinal view in opposition to the canon Episcopi gained ground in certain communities. This fueled a paranoia among certain religious authorities that there was a vast underground conspiracy of witches determined to overthrow Christianity. Women beyond child-bearing years provided an easy target and were scapegoated and blamed for famines, plague, warfare, and other problems. Having prurient and orgiastic elements helped ensure that these stories would be relayed to others.