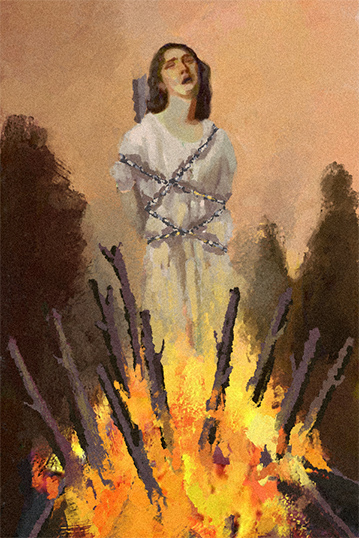

Death by burning

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment for and warning against crimes such as treason, heresy, and witchcraft. The best-known execution of this type is burning at the stake, where the condemned is bound to a large wooden stake and a fire lit beneath.

Effects

In the process of being burned to death, a body experiences burns to exposed tissue, changes in content and distribution of body fluid, fixation of tissue, and shrinkage (especially of the skin). Internal organs may be shrunken due to fluid loss. Shrinkage and contraction of the muscles may cause joints to flex and the body to adopt the "pugilistic stance" (boxer stance), with the elbows and knees flexed and the fists clenched. Shrinkage of the skin around the neck may be severe enough to strangle a victim.

The amount of pain experienced is greatest at the beginning of the burning process before the flame burns the nerves, after which the skin does not hurt. Many victims die quickly from suffocation as hot gases damage the respiratory tract. Those who survive the burning frequently die within days as the lungs' alveoli fill with fluid and the victim dies of pulmonary edema.

Use in Antiquity

Babylon

The 18th-century BCE law code promulgated by Babylonian King Hammurabi specifies several crimes in which death by burning was thought appropriate. Looters of houses on fire could be cast into the flames, and priestesses who abandoned cloisters and began frequenting inns and taverns could also be punished by being burnt alive. Furthermore, a man who began committing incest with his mother after the death of his father could be ordered to be burned alive.

Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, several incidents of burning alive perceived rebels are attested to. Senusret I (r. 1971–1926 BCE) is said to have rounded up the rebels in campaign, and burnt them as human torches. Under the civil war flaring under Takelot II more than a thousand years later, the Crown Prince Osorkon showed no mercy, and burned several rebels alive. On the statute books, at least, women committing adultery might be burned to death.

Jon Manchip White, however, did not think capital judicial punishments were often carried out, pointing to the fact that the pharaoh had to personally ratify each verdict. Authors have speculated that after the harem conspiracy in which pharaoh Ramesses III was assassinated, the non-nobles who had participated in the plot were burned alive, because the Egyptians believed that without a physical body, one could not enter the afterlife. This would explain why Pentawere, the prince whose mother instigated the would-be coup, was most likely strangled or hanged himself; as a royal, he would have been spared this ultimate fate.

Hebrew tradition

In Genesis 38, Judah orders Tamar—the widow of his son, living in her father's household—to be burned when she is believed to have become pregnant by an extramarital sexual relation. Tamar saves herself by proving that Judah is himself the father of her child. In the Book of Jubilees, the same story is told, with some intriguing differences, according to Caryn A. Reeder. In Genesis, Judah is exercising his patriarchal power at a distance, whereas he and the relatives seem more actively involved in Tamar's impending execution.

In Hebraic law, death by burning was prescribed for ten forms of sexual crimes: the imputed crime of Tamar, namely that a married daughter of a priest commits adultery, and nine versions of relationships considered as incestuous, such as having sex with one's own daughter, or granddaughter, but also having sex with one's mother-in-law or with one's wife's daughter.

Use in Ancient Rome

According to ancient reports, Roman authorities executed many of the early Christian martyrs by burning. An example of this is the earliest chronicle of a martyrdom, that of Polycarp. Sometimes this was by means of the tunica molesta, a flammable tunic:

... the Christian, stripped naked, was forced to put on a garment called the tunica molesta, made of papyrus, smeared on both sides with wax, and was then fastened to a high pole, from the top of which they continued to pour down burning pitch and lard, a spike fastened under the chin preventing the excruciated victim from turning the head to either side, so as to escape the liquid fire, until the whole body, and every part of it, was literally clad and cased in flame.

In 326, Constantine the Great promulgated a law that increased the penalties for parentally non-sanctioned "abduction" of their girls, and concomitant sexual intercourse/rape. The man was to be burnt alive without the possibility of appeal, and the girl was to receive the same treatment if she had participated willingly. Nurses who had corrupted their female wards and led them to sexual encounters were to have molten lead poured down their throats. In the same year, Constantine also passed a law that said if a woman had sexual relations with her own slave, both were to be subjected to capital punishment, the slave by burning (if the slave himself reported the offense — presumably having been raped — he was to be set free).

In 390 CE, Emperor Theodosius issued an edict against male prostitutes and brothels offering such services; those found guilty should be burned alive.

Use by European Christians

Once they had assumed power across Europe, Christians quickly adopted the practices of their former Roman oppressors by instituting burning for a wide range of confirmed or perceived offenses. Civil authorities burned persons judged to be heretics under the medieval Inquisition. Burning heretics had become customary practice in the latter half of the twelfth century in continental Europe, and death by burning became statutory punishment from the early 13th century.

As some in England at the start of the 15th century grew weary of the teachings of John Wycliffe and the Lollards, kings, priests, and parliaments reacted with fire. In 1401, Parliament passed the De heretico comburendo act, which can be loosely translated as "Regarding the burning of heretics." Lollard persecution would continue for over a hundred years in England. The Fire and Faggot Parliament met in May 1414 at Grey Friars Priory in Leicester to lay out the notorious Suppression of Heresy Act 1414, enabling the burning of heretics by making the crime enforceable by the Justices of the peace. John Oldcastle, a prominent Lollard leader, was not saved from the gallows by his old friend King Henry V. Oldcastle was hanged and his gallows burned in 1417.

Jan Hus was burned at the stake after being accused at the Roman Catholic Council of Constance (1414–18) of heresy. The ecumenical council also decreed that the remains of John Wycliffe, dead for 30 years, should be exhumed and burned. (This posthumous execution was carried out in 1428.)

Queen Mary I of England ordered hundreds of Protestants burnt at the stake during her reign (1553–58) in what would be known as the "Marian Persecutions" earning her the epithet of "Bloody" Mary. Many of those executed by Mary and the Roman Catholic Church are listed in Actes and Monuments, written by Foxe in 1563 and 1570.

Witch-Hunts

Burning was used during the witch-hunts of Europe, although hanging was the preferred style of execution in England and Wales. The penal code known as the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (1532) decreed that sorcery throughout the Holy Roman Empire should be treated as a criminal offence, and if it purported to inflict injury upon any person the witch was to be burnt at the stake. In 1572, Augustus, Elector of Saxony imposed the penalty of burning for witchcraft of every kind, including simple divination.

Based on meticulous study of trial records, ecclesiastical and inquisitorial registers and so on, as well as on the utilization of modern statistical methods, the specialist research community on witchcraft has reached an agreement for roughly 40,000–50,000 people executed for witchcraft in Europe in total, and by no means all of them executed by being burned alive. Furthermore, it is solidly established that the peak period of witch-hunts was the century 1550–1650, with a slow increase preceding it, from the 15th century onward, as well as a sharp drop following it, with "witch-hunts" having basically fizzled out by the first half of the 18th century.

People executed by burning

- The Knights Templar (1307) - Heresy

- Jan Hus (1415) - Heresy

- Joan of Arc (1431) - Heresy

- Michael Servetus (1553) - Heresy

- Agnes Sampson (1591) - Witchcraft

- Margaret Aitken (1597) - Witchcraft

- Giordano Bruno (1600) - Heresy

- Urbain Grandier (1634) - Witchcraft

- La Voisin (1680) - Witchcraft