Difference between revisions of "Witch-hunt"

Occultwiki (talk | contribs) |

Occultwiki (talk | contribs) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today. | The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today. | ||

==Cause of witch-hunting activities== | |||

Harvard professor George. L. Kittredge, author of the book ''Witchcraft in Old and New England'' stated, "Witch-hunting never flourishes unless the common people are eager for it." He believed that witch-hunting had nothing to do with actual acts of [[black magic]], but were motivated by a collective fear and anxiety found beneath the surface of certain societies at certain times. At its core, these violent acts were the result of male misogynistic attitudes and a desire to assert their power over women. | |||

This is borne out in the nature of the laws under which witches were arrested and tried. The criminal offense of ''maleficium'' required only that the witch in question caused sensations of fear and terror among members of the populace. Thus, if anyone felt uneasy about a particular woman's attitude or behavior, they only needed to claim they "felt afraid" in order for the case to proceed. Spells, [[familiar]]s, and [[diabolical pact]]s were merely accessories to the crime. | |||

''Maleficium'' permitted men of authority to hunt women like animals simply because they were viewed as an enemy of masculine power. | |||

==Early European witch-hunts== | ==Early European witch-hunts== | ||

The rise of witch-hunts at the end of the medieval period, taking place with at least partial support or at least tolerance on the part of the Church, was accompanied with a number of developments in [[Christianity|Christian]] doctrine, for example, the recognition of the existence of [[witchcraft]] as a form of [[Satan]]ic influence and its classification as a [[heresy]]. As Renaissance occultism gained traction among the educated classes, the belief in witchcraft, which in the medieval period had been part of the folk religion of the uneducated rural population at best, was incorporated into an increasingly comprehensive theology of Satan as the ultimate source of all ''maleficium''. | The rise of witch-hunts at the end of the medieval period, taking place with at least partial support or at least tolerance on the part of the Church, was accompanied with a number of developments in [[Christianity|Christian]] doctrine, for example, the recognition of the existence of [[witchcraft]] as a form of [[Satan]]ic influence and its classification as a [[heresy]]. As Renaissance occultism gained traction among the educated classes, the belief in witchcraft, which in the medieval period had been part of the folk religion of the uneducated rural population at best, was incorporated into an increasingly comprehensive theology of Satan as the ultimate source of all ''maleficium''. | ||

In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII issued ''Summis desiderantes affectibus'', a Papal bull authorizing the "correcting, imprisoning, punishing and chastising" of devil-worshippers who have "slain infants", among other crimes. He did so at the request of inquisitor Heinrich Kramer, who had been refused permission by the local bishops in Germany to investigate. Three years later in 1487, Kramer published the notorious ''[[Malleus Maleficarum]]'' (lit., ''Hammer against the Evildoers'') which, because of the newly invented printing presses, enjoyed a wide readership. It was reprinted in 14 editions by 1520 and became unduly influential in the secular courts. | In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII issued ''Summis desiderantes affectibus'', a Papal bull authorizing the "correcting, imprisoning, punishing and chastising" of devil-worshippers who have "slain infants", among other crimes. He did so at the request of [[Inquisition|inquisitor]] Heinrich Kramer, who had been refused permission by the local bishops in Germany to investigate. Three years later in 1487, Kramer published the notorious ''[[Malleus Maleficarum]]'' (lit., ''Hammer against the Evildoers'') which, because of the newly invented printing presses, enjoyed a wide readership. It was reprinted in 14 editions by 1520 and became unduly influential in the secular courts. | ||

==Early Modern Period witch-hunts== | ==Early Modern Period witch-hunts== | ||

Latest revision as of 23:41, 2 August 2025

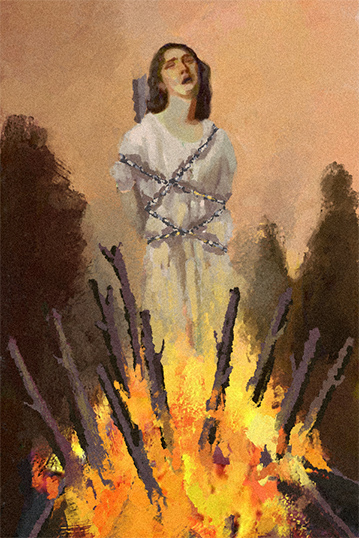

A witch-hunt is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America took place in the Early Modern period or about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 50,000 executions.

The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today.

Cause of witch-hunting activities

Harvard professor George. L. Kittredge, author of the book Witchcraft in Old and New England stated, "Witch-hunting never flourishes unless the common people are eager for it." He believed that witch-hunting had nothing to do with actual acts of black magic, but were motivated by a collective fear and anxiety found beneath the surface of certain societies at certain times. At its core, these violent acts were the result of male misogynistic attitudes and a desire to assert their power over women.

This is borne out in the nature of the laws under which witches were arrested and tried. The criminal offense of maleficium required only that the witch in question caused sensations of fear and terror among members of the populace. Thus, if anyone felt uneasy about a particular woman's attitude or behavior, they only needed to claim they "felt afraid" in order for the case to proceed. Spells, familiars, and diabolical pacts were merely accessories to the crime.

Maleficium permitted men of authority to hunt women like animals simply because they were viewed as an enemy of masculine power.

Early European witch-hunts

The rise of witch-hunts at the end of the medieval period, taking place with at least partial support or at least tolerance on the part of the Church, was accompanied with a number of developments in Christian doctrine, for example, the recognition of the existence of witchcraft as a form of Satanic influence and its classification as a heresy. As Renaissance occultism gained traction among the educated classes, the belief in witchcraft, which in the medieval period had been part of the folk religion of the uneducated rural population at best, was incorporated into an increasingly comprehensive theology of Satan as the ultimate source of all maleficium.

In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII issued Summis desiderantes affectibus, a Papal bull authorizing the "correcting, imprisoning, punishing and chastising" of devil-worshippers who have "slain infants", among other crimes. He did so at the request of inquisitor Heinrich Kramer, who had been refused permission by the local bishops in Germany to investigate. Three years later in 1487, Kramer published the notorious Malleus Maleficarum (lit., Hammer against the Evildoers) which, because of the newly invented printing presses, enjoyed a wide readership. It was reprinted in 14 editions by 1520 and became unduly influential in the secular courts.

Early Modern Period witch-hunts

The witch trials in Early Modern Europe came in waves and then subsided. There were trials in the 15th and early 16th centuries, but then the witch scare went into decline, before becoming a major issue again and peaking in the 17th century; particularly during the Thirty Years War. What had previously been a belief that some people possessed supernatural abilities (which were sometimes used to protect the people), now became a sign of a pact between the people with supernatural abilities and the Devil.

To justify the killings, Protestant Christianity and its proxy secular institutions deemed witchcraft as being associated to wild Satanic ritual parties in which there was naked dancing and cannibalistic infanticide. It was also seen as heresy for going against the first of the ten commandments ("You shall have no other gods before me") or as violating majesty, in this case referring to the divine majesty, not the worldly. Further scripture was also frequently cited, especially the Exodus decree that "thou shalt not suffer a witch to live" (Exodus 22:18), which many supported.

Once a case was brought to trial, the prosecutors hunted for accomplices. The use of magic was considered wrong, not because it failed, but because it worked effectively for the wrong reasons. Witchcraft was a normal part of everyday life. Witches were often called for, along with religious ministers, to help the ill or deliver a baby. They held positions of spiritual power in their communities. When something went wrong, no one questioned either the ministers or the power of the witchcraft. Instead, they questioned whether the witch intended to inflict harm or not.

Witch-hunts were seen across early modern Europe, but the most significant area of witch-hunting in modern Europe is often considered to be central and southern Germany. Germany was a late starter in terms of the numbers of trials, compared to other regions of Europe. Witch-hunts first appeared in large numbers in southern France and Switzerland during the 14th and 15th centuries. The peak years of witch-hunts in southwest Germany were from 1561 to 1670.

The first major persecution in Europe, when witches were caught, tried, convicted, and burned in the imperial lordship of Wiesensteig in southwestern Germany, is recorded in 1563 in a pamphlet called "True and Horrifying Deeds of 63 Witches". Witchcraft persecution spread to all areas of Europe. Learned European ideas about witchcraft and demonological ideas, strongly influenced the hunt for witches in the North.

In Denmark, the burning of witches increased following the reformation of 1536. Christian IV of Denmark, in particular, encouraged this practice, and hundreds of people were convicted of witchcraft and burnt. In the district of Finnmark, northern Norway, severe witchcraft trials took place during the period 1600–1692. A memorial of international format, Steilneset Memorial, has been built to commemorate the victims of the Finnmark witchcraft trials. In England, the Witchcraft Act of 1542 regulated the penalties for witchcraft.

In England and Scotland

In the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, over 70 people were accused of witchcraft on account of bad weather when James VI of Scotland, who shared the Danish king's interest in witch trials, sailed to Denmark in 1590 to meet his betrothed Anne of Denmark. According to a widely circulated pamphlet, "Newes from Scotland," James VI personally presided over the torture and execution of Doctor Fian. Indeed, James published a witch-hunting manual, Daemonologie, which contains the famous dictum: "Experience daily proves how loath they are to confess without torture." Later, the Pendle witch trials of 1612 joined the ranks of the most famous witch trials in English history.

In England, witch-hunting would reach its apex in 1644 to 1647 due to the efforts of Puritan Matthew Hopkins. Although operating without an official Parliament commission, Hopkins (calling himself Witchfinder General) and his accomplices charged hefty fees to towns during the English Civil War. Hopkins' witch-hunting spree was brief but significant: 300 convictions and deaths are attributed to his work. Hopkins wrote a book on his methods, describing his fortuitous beginnings as a witch-hunter, the methods used to extract confessions, and the tests he employed to test the accused: stripping them naked to find the Witches' mark, the "swimming" test, and pricking the skin.

The swimming test, which included throwing a witch, who was strapped to a chair, into a bucket of water to see if she floated, was discontinued in 1645 due to a legal challenge.

In North America

Witch-hunts began to occur in North America while Hopkins was hunting witches in England. In 1645, forty-six years before the notorious Salem Witch Trials, Springfield, Massachusetts experienced America's first accusations of witchcraft when husband and wife Hugh and Mary Parsons accused each other of witchcraft. In America's first witch trial, Hugh was found innocent, while Mary was acquitted of witchcraft but she was still sentenced to be hanged as punishment for the death of her child. She died in prison. About eighty people throughout England's Massachusetts Bay Colony were accused of practicing witchcraft; thirteen women and two men were executed in a witch-hunt that occurred throughout New England and lasted from 1645 to 1663.

The 1647 book, The Discovery of Witches (not to be confused with the earlier tome, The Discoverie of Witchcraft), soon became an influential legal text. The book was used in the American colonies as early as May 1647, when Margaret Jones was executed for witchcraft in Massachusetts, the first of 17 people executed for witchcraft in the Colonies from 1647 to 1663.