Heaven

Heaven is a common religious cosmological or transcendent supernatural place where beings such as deities, angels, souls, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or reside. According to the beliefs of some religions, heavenly beings can descend to Earth or incarnate and earthly beings can ascend to Heaven in the afterlife or, in exceptional cases, enter Heaven without dying.

Heaven is often described as a "highest place," the holiest place, a paradise, in contrast to hell or the underworld or the "low places" and universally or conditionally accessible by earthly beings according to various standards of divinity, goodness, piety, faith, or other virtues or right beliefs or simply divine will.

At least in the Abrahamic religions of Christianity, Islam, and some schools of Judaism, as well as Zoroastrianism, heaven is the realm of afterlife where good actions in the previous life are rewarded for eternity (hell being the place where bad behavior is punished).

Etymology

The modern English word heaven is derived from the earlier (Middle English) heven (attested 1159); this in turn was developed from the previous Old English form heofon. By about 1000, heofon was being used in reference to the Christianized "place where God dwells," but originally, it had signified "sky, firmament."

It may ultimately have derived from a Proto-Indo-European root *h₂éḱmō ("stone" and, possibly, "heavenly vault") at the origin of this word, which then would have as cognates:

- ancient Greek ἄκμων (ákmōn "anvil, pestle; meteorite")

- Persian آسمان (âsemân, âsmân "stone, sling-stone; sky, heaven")

- Sanskrit अश्मन् (aśman "stone, rock, sling-stone; thunderbolt; the firmament")

Mesopotamian religions

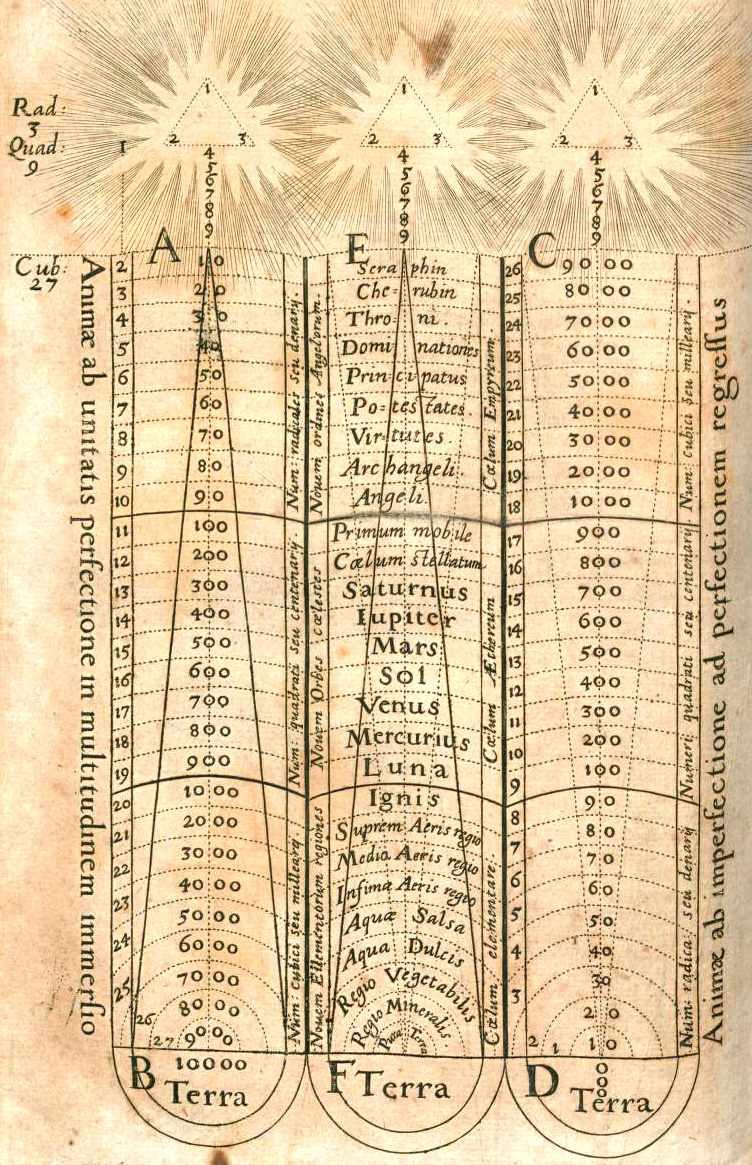

The ancient Mesopotamians regarded the sky as a series of domes (usually three, but sometimes seven) covering the flat Earth. Each dome was made of a different kind of precious stone. The lowest dome of heaven was made of jasper and was the home of the stars.

In ancient Near Eastern cultures in general and in Mesopotamia in particular, humans had little to no access to the divine realm. Heaven and Earth were separated by their very nature; humans could see and be affected by elements of the lower heaven, such as stars and storms, but ordinary mortals could not go to Heaven because it was the abode of the gods alone.

All souls went to the same afterlife, and a person's actions during life had no impact on how he would be treated in the world to come. Nonetheless, funerary evidence indicates that some people believed that Inanna had the power to bestow special favors upon her devotees in the afterlife. Despite the separation between heaven and earth, humans sought access to the gods through oracles and omens. The gods were believed to live in Heaven, but also in their temples, which were seen as the channels of communication between Earth and Heaven, which allowed mortal access to the gods.

The ancient Hittites believed that some deities lived in Heaven while others lived in remote places on Earth, such as mountains, where humans had little access.

Zoroaster, the Zoroastrian prophet who introduced the Gathas, spoke of the existence of Heaven and Hell.

Old Testament description

As in other ancient Near Eastern cultures, in the Hebrew Bible, the universe is commonly divided into two realms: heaven (šāmayim) and earth (’ereṣ). Sometimes a third realm is added: either "sea"," "water under the earth," or sometimes a vague "land of the dead" that is never described in depth. The structure of heaven itself is not fully described in the Hebrew Bible, but the fact that the Hebrew word šāmayim is plural has been interpreted by scholars as an indication that the ancient Israelites envisioned the heavens as having multiple layers, much like the ancient Mesopotamians.

The Hebrew Bible depicts Heaven as a place that is inaccessible to humans. Although some prophets are occasionally granted temporary visionary access to heaven, they hear only God's deliberations concerning the Earth and learn nothing of what Heaven is like. There is almost no mention in the Hebrew Bible of Heaven as a possible afterlife destination for human beings, who are instead described as "resting" in Sheol. The only two possible exceptions to this are Enoch, who is described in Genesis 5:24[44] as having been "taken" by God, and the prophet Elijah, who is described in 2 Kings 2:11 as having ascended to Heaven in a chariot of fire.

The God of the Israelites is described as ruling both Heaven and Earth. A number of passages throughout the Hebrew Bible indicate that Heaven and Earth will one day come to an end. This view is paralleled in other ancient Near Eastern cultures, which also regarded Heaven and Earth as vulnerable and subject to dissolution. However, the Hebrew Bible differs from other ancient Near Eastern cultures in that it portrays the God of Israel as independent of creation and unthreatened by its potential destruction.

Heaven in Christianity

Descriptions of Heaven in the New Testament are more fully developed than those in the Old Testament, but are still generally vague. As in the Old Testament, in the New Testament God is described as the ruler of Heaven and Earth, but his power over the Earth is challenged by Satan.

Modern scholars agree that the Kingdom of God was an essential part of the teachings of the historical Jesus, but there is no agreement on what this kingdom was. None of the gospels record Jesus as having explained exactly what the phrase "Kingdom of God" means. The most likely explanation for this apparent omission is that the Kingdom of God was a commonly understood concept that required no explanation.

Jews in Judea during the early first century believed that God reigns eternally in Heaven, but many also believed that God would eventually establish his kingdom on earth as well. Because God's Kingdom was believed to be superior to any human kingdom, this meant that God would necessarily drive out the Romans, who ruled Judea, and establish his own direct rule over the Jewish people. In the teachings of the historical Jesus, people are expected to prepare for the coming of the Kingdom of God by living moral lives. Jesus's commands for his followers to adopt lifestyles of moral perfectionism are found in many passages throughout the Synoptic Gospels.

Traditionally, Christianity has taught that Heaven is the location of the throne of God as well as the holy angels, although this is in varying degrees considered metaphorical. It is considered a state or condition of existence (rather than a particular place somewhere in the cosmos) of the supreme fulfillment of theosis in the beatific vision of the Godhead. In most forms of Christianity, Heaven is also understood as the abode for the redeemed dead in the afterlife, usually a temporary stage before the resurrection of the dead and the saints' return to the New Earth.

The resurrected Jesus is said to have ascended to Heaven where he now sits at the Right Hand of God and will return to Earth in the Second Coming. Various people have been said to have entered Heaven while still alive, including Enoch, Elijah and Jesus, after his resurrection. According to Roman Catholic teaching, Mary, mother of Jesus, is also said to have been assumed into Heaven and is titled the Queen of Heaven.

Heaven in Judaism

While the concept of Heaven (malkuth hashamaim מלכות השמים, the Kingdom of Heaven) is much discussed in Christian thought, the Jewish concept of the afterlife, sometimes known as olam haba, the World-to-come, is not discussed as often. The Torah has little to say on the subject of survival after death, but by the time of the rabbis two ideas had made inroads among the Jews: one, which is probably derived from Greek thought, is that of the immortal soul which returns to its creator after death; the other, which is thought to be of Persian origin, is that of resurrection of the dead.

Judaism holds that the righteous of all nations have a share in the World-to-come.

Judaism offers no clear teaching about the destiny which lies in wait for the individual after death and its attitude to life after death has been expressed as follows: "For the future is inscrutable, and the accepted sources of knowledge, whether experience, or reason, or revelation, offer no clear guidance about what is to come. The only certainty is that each man must die – beyond that we can only guess."

Heaven in Islam

Similar to Jewish traditions such as the Talmud, the Qur'an and Hadith frequently mention the existence of seven samāwāt (سماوات), meaning 'heaven, sky, celestial sphere', and cognate with Hebrew shamāyim (שמים). Some of the verses in the Qur'an mentioning the samaawat are 41:12, 65:12 and 71:15. Sidrat al-Muntaha, a large enigmatic Lote tree, marks the end of the seventh heaven and the utmost extremity for all of God's creatures and heavenly knowledge. One interpretation of "heavens" is that all the stars and galaxies (including the Milky Way) are part of the "first heaven", and "beyond that six still bigger worlds are there," which have yet to be discovered by scientists.

According to Shi'ite sources, Ali mentioned the names of the seven heavens as below:

- Rafi' (رفیع) the least heaven (سماء الدنیا)

- Qaydum (قیدوم)

- Marum (ماروم)

- Arfalun (أرفلون)

- Hay'oun (هيعون)

- Arous (عروس)

- Ajma' (عجماء)

An afterlife destination of the righteous is conceived in Islam as Jannah (Arabic: جنة "Garden of Eden" translated as "paradise"). Regarding Eden or paradise the Quran says, "The description of the Paradise promised to the righteous is that under it rivers flow; eternal is its fruit as well as its shade. That is the ˹ultimate˺ outcome for the righteous. But the outcome for the disbelievers is the Fire!"

Paradise is described primarily in physical terms as a place where every wish is immediately fulfilled when asked. Islamic texts describe immortal life in Jannah as happy, without negative emotions. Those who dwell in Jannah are said to wear costly apparel, partake in exquisite banquets, and recline on couches inlaid with gold or precious stones. Inhabitants will rejoice in the company of their parents, spouses, and children. In Islam if one's good deeds outweigh one's sins then one may gain entrance to paradise only through God's mercy. Conversely, if one's sins outweigh their good deeds they are sent to hell. The more good deeds one has performed the higher the level of Jannah one is directed to.

Heaven in the Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith regards the conventional description of heaven (and hell) as a specific place as symbolic. The Baháʼí writings describe heaven as a "spiritual condition" where closeness to God is defined as heaven; conversely hell is seen as a state of remoteness from God. Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, has stated that the nature of the life of the soul in the afterlife is beyond comprehension in the physical plane, but has stated that the soul will retain its consciousness and individuality and remember its physical life; the soul will be able to recognize other souls and communicate with them.

Chinese religions

In the native Chinese Confucian traditions, heaven (Tian) is an important concept, where the ancestors reside and from which emperors drew their mandate to rule in their dynastic propaganda, for example, as evidenced by their title "The Son of Heaven."

Heaven is a key concept in Chinese mythology, philosophies, and religions, and is on one end of the spectrum a synonym of Shangdi ("Supreme Deity") and on the other naturalistic end, a synonym for nature and the sky. The Chinese term for "heaven", Tian (天), derives from the name of the supreme deity of the Zhou dynasty. Heaven is affected by people's doings, and having personality, is happy and angry with them. Heaven blesses those who please it and sends calamities upon those who offend it. Heaven was also believed to transcend all other spirits and gods, with Confucius asserting, "He who offends against Heaven has none to whom he can pray."

Other philosophers born around the time of Confucius such as Mozi took an even more theistic view of heaven, believing that heaven is the divine ruler, just as the Son of Heaven (the King of Zhou) is the earthly ruler. Mozi believed that spirits and minor gods exist, but their function is merely to carry out the will of heaven, watching for evil-doers and punishing them.

Buddhism

In Buddhism there are several heavens, all of which are still part of samsara (illusionary reality). Those who accumulate good karma may be reborn in one of them. However, their stay in heaven is not eternal—eventually they will use up their good karma and will undergo rebirth into another realm, as a human, animal or other being. Because heaven is temporary and part of samsara, Buddhists focus more on escaping the cycle of rebirth and reaching enlightenment (nirvana). Nirvana is not a heaven but a mental state.

According to Buddhist cosmology the universe is impermanent and beings transmigrate through several existential "planes" in which this human world is only one "realm" or "path".

Hinduism

Attaining heaven is not the final pursuit in Hinduism as heaven itself is ephemeral and related to physical body. Only being tied by the bhoot-tattvas, heaven cannot be perfect either and is just another name for pleasurable and mundane material life. According to Hindu cosmology, above the earthly plane, are other planes. Swarga Loka, meaning Good Kingdom, is the general name for heaven in Hinduism, a heavenly paradise of pleasure, where most of the Hindu Devatas (Deva) reside along with the king of Devas, Indra, and beatified mortals. Since heavenly abodes are also tied to the cycle of birth and death, any dweller of heaven or hell will again be recycled to a different plane and in a different form per the karma and "maya" i.e. the illusion of Samsara. This cycle is broken only by self-realization by the Jivatma. This self-realization is Moksha (Turiya, Kaivalya).

The concept of moksha is unique to Hinduism. Moksha stands for liberation from the cycle of birth and death and final communion with Brahman. With moksha, a liberated soul attains the stature and oneness with Brahman or Paramatma.

Other religions

The Nahua people such as the Aztecs, Chichimecs and the Toltecs believed that the heavens were constructed and separated into 13 levels. Each level had from one to many Lords living in and ruling these heavens. Most important of these heavens was Omeyocan (Place of Two). The Thirteen Heavens were ruled by Ometeotl, the dual Lord, creator of the Dual-Genesis who, as male, takes the name Ometecuhtli (Two Lord), and as female is named Omecihuatl (Two Lady).

In Māori mythology, the heavens are divided into a number of realms. Different tribes number the heaven differently, with as few as two and as many as fourteen levels

It is believed in Theosophy, founded mainly by Helena Blavatsky, that each religion (including Theosophy) has its own individual heaven in various regions of the upper astral plane that fits the description of that heaven that is given in each religion, to which a soul that has been good in their previous life on Earth will go.

View of neuroscience

Many neuroscientists and neurophilosophers, such as Daniel Dennett, believe that consciousness is dependent upon the functioning of the brain and death is a cessation of consciousness, which would rule out heaven. Scientific research has discovered that some areas of the brain, like the reticular activating system or the thalamus, appear to be necessary for consciousness, because dysfunction of or damage to these structures causes a loss of consciousness.

In Inside the Neolithic Mind (2005), Lewis-Williams and Pearce argue that many cultures around the world and through history neurally perceive a tiered structure of heaven, along with similarly structured circles of hell. The reports match so similarly across time and space that Lewis-Williams and Pearce argue for a neuroscientific explanation, accepting the precepts as real neural activations and subjective percepts during particular altered states of consciousness.

Many people who come close to death and have near-death experiences report meeting relatives or entering "the Light" in an otherworldly dimension, which shares similarities with the religious concept of heaven. Even though there are also reports of distressing experiences and negative life-reviews, which share some similarities with the concept of hell, the positive experience of meeting or entering "the Light" is reported as an immensely intense feeling of a state of love, peace and joy beyond human comprehension. Together with this intensely positive-feeling state, people who have near-death experiences also report that consciousness or a heightened state of awareness seems as if it is at the heart of experiencing a taste of "heaven."

Representation in fiction

Works of literary fiction have included numerous conceptions of Heaven.

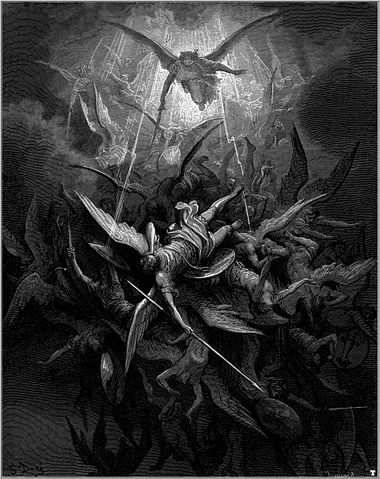

Perhaps the two most famous descriptions of Heaven are given in Dante Alighieri's Paradiso (of the Divine Comedy) and John Milton's Paradise Lost.