Black magic

Black magic has traditionally referred to the use of supernatural powers or magic for evil and selfish purposes; or magic associated with the Devil or other evil spirits. It is also sometimes referred to as the "left-hand path," (its right-hand path counterpart being benevolent white magic).

In modern times, some find that the definition of black magic has been convoluted by people who define magic or ritualistic practices that they disapprove of as black magic.

History

During the Renaissance, many magical practices and rituals were considered evil or irreligious and by extension, black magic in the broad sense. Witchcraft and non-mainstream esoteric study were prohibited and targeted by the Inquisition. As a result, natural magic developed as a way for thinkers and intellectuals, like Marsilio Ficino, abbot Johannes Trithemius and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, to advance esoteric and ritualistic study (though still often in secret) without significant persecution.

While "natural magic" became popular among the educated and upper classes of the 16th and 17th century, ritual magic and folk magic remained subject to persecution. 20th century author Montague Summers generally rejects the definitions of "white" and "black" magic as "contradictory," though he highlights the extent to which all magic, regardless of intent, was considered "black," even magic involving angels, because it attempted to subvert the will of God in favor of the magician.

William Perkins' 1608 instructions in regard to magic of any kind:

All witches "convicted by the Magistrate" should be executed. He allows no exception and under this condemnation fall "all Diviners, Charmers, Jugglers, all Wizards, commonly called wise men or wise women." All those purported "good Witches which do not hurt but good, which do not spoil and destroy, but save and deliver" should come under the extreme sentence.

In particular, though, the term was most commonly reserved for those accused of invoking demons and other evil spirits, those hexing or cursing their neighbors, those using magic to destroy crops, and those capable of leaving their earthly bodies and travelling great distances in spirit (to which the Malleus Maleficarum "devotes one long and important chapter"), usually to engage in devil-worship. Summers also highlights the etymological development of the term nigromancer, in common use from 1200 to approximately 1500, (Latin: niger, black; Greek: μαντεία, divination), broadly "one skilled in the black arts."

Modern definition

In a modern context, the line between white magic and black magic is somewhat clearer and most modern definitions focus on intent rather than practice. There is also an extent to which many modern Wicca and witchcraft practitioners have sought to distance themselves from those intent on practising black magic. Those who seek to do harm or evil are less likely to be accepted into mainstream Wiccan circles or covens in an era where benevolent magic is increasingly associated with New Age beliefs and practices, and self-help spiritualism.

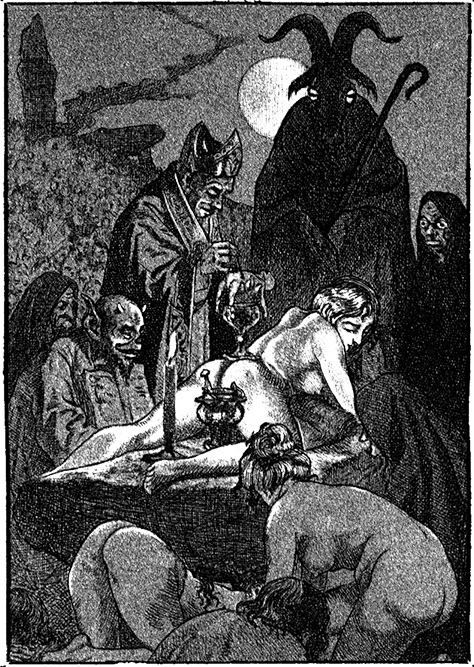

Black magic as Satanism

The influence of popular culture has allowed other practices to be drawn in under the broad banner of black magic, including the concept of Satanism. While the invocation of demons or spirits is an accepted part of black magic, this practice is distinct from the worship or deification of such spiritual beings. However, the two are usually combined in medieval beliefs about witchcraft.

Those lines, though, continue to be blurred by the inclusion of spirit rituals from otherwise white magicians in compilations of work related to Satanism. John Dee's sixteenth century rituals, for example, were included in Anton LaVey's The Satanic Bible (1969) and so some of his practises, otherwise considered white magic, have since been associated with black magic. Dee's rituals themselves were designed to contact spirits in general and angels in particular, which he claimed to have been able to do with the assistance of colleague Edward Kelley.

African diaspora religions

Throughout the western world, especially in countries where a large majority of the population practices Christianity, practitioners of less-known religions are often demonized as practicing black magic. This is especially true among the various African diaspora religions.

Voodoo

In the United States, Voodoo has often been associated with modern black magic; drawn together in popular culture and fiction. However, while hexing or cursing may be accepted black magic practices, Voodoo has its own distinct history and traditions that have little to do with the traditions of modern witchcraft that developed with European practitioners like Gerald Gardner and Aleister Crowley.

Voodoo tradition makes its own distinction between black and white magic, with sorcerers like the Bokor known for using magic and rituals of both. But their penchant for magic associated with curses, poisons and zombies means they, and Voodoo in general, are regularly associated with black magic in particular.

Afro-Brazilian religions

In Brazil, the majority of the population is Catholic, but a sizable minority adhere to traditional African religious beliefs which have been syncretized with those of Christianity and other mainstream religions.

Because their practices sometimes include animal sacrifice, the use of ritual scarification, and encourage possession by spirits, these are often viewed as black magic by outsiders. However, the adherents of these religious traditions, such as followers of Candomblé and Umbanda distinguish their magical practices from those of "evil" magic such as Quimbanda, which specifically seeks to work with demonic entities.

Practices

During his period of scholarship, A.E. Waite provided a comprehensive account of black magic practices, rituals and traditions in The Book of Black Magic and of Pacts. Waite claimed that the following forms of magic were explicitly evil:

- True name spells - The theory that knowing a person's true name allows control over that person.

- Immortality rituals - Because of the need to test the results, the subjects must be killed. Even a spell to extend life may not be entirely good, especially if it draws life energy from another to sustain the spell.

- Necromancy – Any magic having to do with death itself.

- Curses and hexes – A curse can be as simple as wishing something bad would happen to someone, or as complicated as performing a complex ritual to ensure that someone dies.