Halloween

Halloween or Hallowe'en (less commonly known as All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve) is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints' Day. It begins the observance of Allhallowtide, the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed.

Origins

In the 8th century, Pope Gregory III (731–741) founded an oratory in St Peter's for the relics "of the holy apostles and of all saints, martyrs and confessors." By 800, there is evidence that churches in Ireland and Northumbria were holding a feast commemorating all saints on 1 November.

Alcuin of Northumbria, a member of Charlemagne's court, may then have introduced this 1 November date in the Frankish Empire. In 835, it became the official date in the Frankish Empire. Some suggest this was due to Celtic influence, while others suggest it was a Germanic idea, although it is claimed that both Germanic and Celtic-speaking peoples commemorated the dead at the beginning of winter. They may have seen it as the most fitting time to do so, as it is a time of 'dying' in nature.

By the end of the 12th century, the celebration had become known as the holy days of obligation in Western Christianity and involved such traditions as ringing church bells for souls in purgatory. It was also "customary for criers dressed in black to parade the streets, ringing a bell of mournful sound and calling on all good Christians to remember the poor souls." Groups of poor people, often children, would go door-to-door during Allhallowtide, collecting soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the dead, especially the souls of the givers' friends and relatives. This was called "souling." Soul cakes were also offered for the souls themselves to eat, or the 'soulers' would act as their representatives. While souling, Christians would carry "lanterns made of hollowed-out turnips," which could have originally represented souls of the dead.

On All Saints' and All Souls' Day during the 19th century, candles were lit in homes in Ireland, Flanders, Bavaria, and in Tyrol, where they were called "soul lights," that served "to guide the souls back to visit their earthly homes." In many of these places, candles were also lit at graves on All Souls' Day. In Brittany, libations of milk were poured on the graves of kinfolk, or food would be left overnight on the dinner table for the returning souls; a custom also found in Tyrol and parts of Italy.

Today's Halloween customs are thought to have been influenced by folk customs and beliefs from the Celtic-speaking countries, some of which are believed to have pagan roots. Jack Santino, a folklorist, writes that "there was throughout Ireland an uneasy truce existing between customs and beliefs associated with Christianity and those associated with religions that were Irish before Christianity arrived." The origins of Halloween customs are typically linked to the Gaelic festival Samhain.

Samhain

Samhain is believed to have Celtic pagan origins and some Neolithic passage tombs in Ireland are aligned with the sunrise at the time of Samhain. It is first mentioned in the earliest Irish literature, from the 9th century, and is associated with many important events in Irish mythology.

Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter or the 'darker half' of the year. It was seen as a liminal time, when the boundary between this world and the Otherworld thinned. This meant the Aos Sí, the 'spirits' or 'fairies', could more easily come into this world and were particularly active. Most scholars see them as "degraded versions of ancient gods [...] whose power remained active in the people's minds even after they had been officially replaced by later religious beliefs."

They were both respected and feared, with individuals often invoking the protection of God when approaching their dwellings. At Samhain, the Aos Sí were appeased to ensure the people and livestock survived the winter. Offerings of food and drink, or portions of the crops, were left outside for them. The souls of the dead were also said to revisit their homes seeking hospitality. Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them. The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures. In 19th century Ireland, "candles would be lit and prayers formally offered for the souls of the dead. After this the eating, drinking, and games would begin."

Throughout Ireland and Britain, especially in the Celtic-speaking regions, the household festivities included divination rituals and games intended to foretell one's future, especially regarding death and marriage. Apples and nuts were often used, and customs included apple bobbing, nut roasting, scrying or mirror-gazing, pouring molten lead or egg whites into water, dream interpretation, and others. Special bonfires were lit and there were rituals involving them. Their flames, smoke, and ashes were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers.

In some places, torches lit from the bonfire were carried sunwise around homes and fields to protect them. It is suggested the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic – they mimicked the Sun and held back the decay and darkness of winter. They were also used for divination through pyromancy and to ward off evil spirits. In Scotland, these bonfires and divination games were banned by the church elders in some parishes. In Wales, bonfires were also lit to "prevent the souls of the dead from falling to earth." Later, these bonfires "kept away the Devil."

Symbols

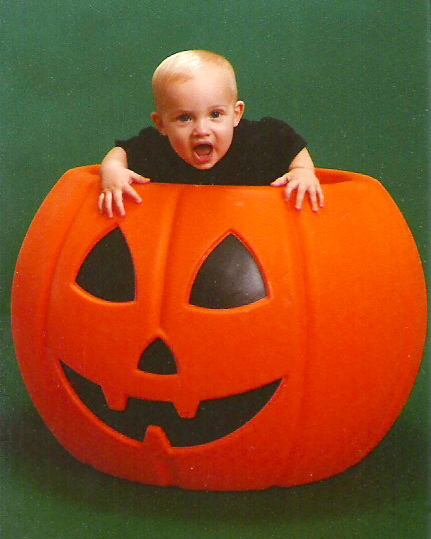

Development of artifacts and symbols associated with Halloween formed over time. There is a popular Irish Christian folktale associated with the jack-o'-lantern, which in folklore is said to represent a "soul who has been denied entry into both heaven and hell."

In Ireland and Scotland, the turnip has traditionally been carved during Halloween, but immigrants to North America used the native pumpkin, which is both much softer and much larger, making it easier to carve than a turnip. The American tradition of carving pumpkins is recorded in 1837 and was originally associated with harvest time in general, not becoming specifically associated with Halloween until the mid-to-late 19th century.

The modern imagery of Halloween comes from many sources, including Christian eschatology, national customs, works of Gothic and horror literature and classic horror films such as Frankenstein (1931) and The Mummy (1932).

One of the earliest works on the subject of Halloween is from Scottish poet John Mayne, who, in 1780, made note of pranks at Halloween; "What fearfu' pranks ensue!", as well as the supernatural associated with the night, "bogles" (ghosts), influencing Robert Burns' "Halloween" (1785).

Elements of the autumn season, such as pumpkins, corn husks, and scarecrows, are also prevalent. Homes are often decorated with these types of symbols around Halloween. Halloween imagery includes themes of death, evil, and mythical monsters. Black cats, which have been long associated with witches, are also a common symbol of Halloween. Black, orange, and sometimes purple are Halloween's traditional colors.

Halloween costumes were traditionally modeled after figures such as vampires, ghosts, skeletons, scary looking witches, and devils. Over time, the costume selection extended to include popular characters from fiction, celebrities, and generic archetypes such as ninjas and princesses.

Neopagan observance

There is no consistent rule or view on Halloween amongst those who describe themselves as Neopagans or Wiccans. Some Neopagans do not observe Halloween, but instead observe Samhain on 1 November, some neopagans do enjoy Halloween festivities, stating that one can observe both "the solemnity of Samhain in addition to the fun of Halloween."

Some neopagans are opposed to the celebration of Hallowe'en, stating that it "trivializes Samhain," and "avoid Halloween, because of the interruptions from trick or treaters."

The Manitoban writes that:

"Wiccans don't officially celebrate Halloween, despite the fact that 31 Oct. will still have a star beside it in any good Wiccan's day planner. Starting at sundown, Wiccans celebrate a holiday known as Samhain. Samhain actually comes from old Celtic traditions and is not exclusive to Neopagan religions like Wicca. While the traditions of this holiday originate in Celtic countries, modern day Wiccans don't try to historically replicate Samhain celebrations. Some traditional Samhain rituals are still practised, but at its core, the period is treated as a time to celebrate darkness and the dead – a possible reason why Samhain can be confused with Halloween celebrations."

Modern celebrations

Modern Halloween celebrations occur in cities around the world, with some of the most well-attended being in:

- Salem, Massachusetts

- West Hollywood, California

- Las Vegas, Nevada

- New Orleans, Louisiana